IV Flush Syringe

Health care professionals routinely use saline flush syringes to keep patients’ IV lines air-free and unobstructed. When manufactured and used correctly, the devices are generally safe, but problems can occur. Manufacturers have recalled more than 30 million IV flush syringes since 2006.

Prefilled saline syringes are common medical devices found in hospitals, clinics and other health care settings. In 2017, various manufacturers churned out an estimated 426 million IV flush syringes.

If you’ve ever had an IV placed, you may have noticed the nurse attaching a small, clear plastic syringe and injecting a clear, colorless fluid to “flush” your IV. Flushing ensures that the IV line is open and not blocked. You might also have noticed a strange taste in your mouth during the flush. This is harmless and happens to many people.

The majority of prefilled saline syringes contain 0.9 percent sodium chloride, which is a mixture of salt and water also known as normal saline. Normal saline is a close approximation to the salt concentration of human blood, so it’s compatible with your body chemistry and maintains good fluid balance.

Less commonly used are heparin IV flush syringes. Heparin syringes contain varying strengths of the anticoagulant diluted in normal saline. Heparin prevents clots from forming inside catheters and nurses sometimes use heparin flushes to “lock” IV devices. Locking is when the nurse flushes an IV line and then caps it off for later use.

A heparin flush generally shouldn’t be used in people with uncontrolled bleeding or low platelet counts because it can worsen those problems or cause other serious reactions.

On several occasions, manufacturers have recalled batches of contaminated IV flush syringes. One of the largest recalls was in 2016 when an IV flush maker recalled hundreds of thousands of syringes linked to a multi-state outbreak of Burkholderia cepacia bloodstream infections.

Uses, Benefits & Risks

Health care providers use IV flushes to clear out intravenous lines that deliver medicine directly into the veins of a patient. Flushes are administered before and after starting IV medication drips or fluids in patients. This ensures the lines stay clean and prevents blockages.

Flushes are also commonly used in between administering multiple medications to ensure the medications won’t react. During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2022, the FDA announced a shortage of prefilled 0.9% sodium chloride IV flush syringes because of increased demand, vendor supply chain challenges and discontinuation of particular flushes.

To flush an IV, a nurse or other health care professional will clean the IV port, remove the syringe from its packaging, expel any air from the syringe and connect the IV flush syringe to the port. Next, they’ll gently inject the flush solution into the IV or catheter. At this time, the nurse may start a medication drip. They’ll flush the line again before starting another drug.

When properly manufactured and used correctly, prefilled saline syringes can make life much easier for health care providers and patients. The devices increase workflow efficiency in care settings and usually decrease the risk of infection. They also decrease the risk of needlestick injuries among health care professionals.

Although saline flushes are well tolerated by most people, complications may occur. In rare cases, for instance, a saline flush can introduce dangerous air bubbles, known as embolisms, into a person’s vein. Poor manufacturer compliance with FDA regulations can result in contamination that leads to outbreaks of infections.

Bacterial Contamination and Other Recalls

Since 2006, IV flush manufacturers have recalled more than 30 million prefilled syringes. The reasons for the recalls have included everything from mislabeling to bacterial contamination.

| Manufacturer, Date & Units | Products | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Medline industries Inc.; Feb. 1, 2018; 90,870 syringes | Medline 0.9 % Sodium Chloride Injection, USP 5 mL in 10 mL Syringe ZR | Improper packaging |

| Nurse Assist Inc.; Oct. 4, 2016; 386,175 syringes | Normal Saline Flush 0.9% USP Sodium Chloride Injection Syringe, 3 ml fill, 5 ml fill and 10 ml fill. Product codes: 1203, 1205, 1210, 1210-BP | Potential contamination with B. cepacia |

| Covidien LLC; Aug. 6, 2015; 207,876 syringes | Monoject 0.9% Saline Flush Prefill Double Pouch. Item Code: 8881570129. | Sterility potentially compromised due to poor packaging process control |

| MRP, LLC dba AMUSA; April 27, 2015; 200,000 syringes | 0.9% Sodium Chloride Injection, USP, Flush Syringe, 10 mL in 12 mL, Sterile, Rx only, Code No. 2T0806 | Incorrect expiration date on label |

| Becton Dickinson & Company; July 22, 2014; 3,088,320 syringes | BD PosiFlush SF Saline Flush Syringe 0.9 Sodium Chloride Injection, USP 10 mL REF 306553 | Reports of open seals found on some flush syringes |

| Covidien LLC; Aug. 16, 2013; 3,565,980 syringes) | Monoject 100 Units/mL Heparin Lock Flush, 12 mL Syringe with 5 mL Fill Product ID: 8881590125; Monoject 0.9% Sodium Chloride Flush Syringe, 12 mL Syringe with 10 mL Fill Product ID: 8881570121 | Prefill flush syringes potentially contained non-sterile water and labeled as saline or heparin |

| Hospira Inc.; Nov. 18, 2011; 5,817,600 syringes | 0.9% Sodium Chloride Injection, USP, pre-filled flush solution, for IV Flush only, sterile fluid path; 10 mL Single-Use Syringe with Male Luer Lock, 100 syringes per pack, 4 packs per case; Made in Costa Rica, Hospira, Inc., Lake Forest, IL 60045 USA; list no. 1978-20 | Contamination: Particulate matter in the fluid identified as the same material as the rubber tip of the syringe plunger |

| Covidien LP; Nov. 15, 2010; 1,356,480 syringes | MONOJECT Prefill Heparin Lock Flush Syringe 10 Unit Heparin, 5 ml in 12 ml syringe Item code 8881580125 | Contamination: The heparin used to manufacture the syringes was produced with an “oversulfated chondroitin sulfate” associated with severe allergic reactions in some patients |

| Excelsior Medical Corp.; Sept. 2, 2010; 13,734,640 syringes | Excelsior Disposable Syringe w/Normal Saline (0.9% sodium chloride) General hospital use | Potential leakage and loss of sterility of 6 ml syringe products |

| B. Braun Medical Inc.; July 30, 2007; 1,325,760 | Normal Saline 10ml in 12ml Syringe and normal Saline 3ml in 12ml Syringe. | Contamination: Particulate matter in product |

| Excelsior Medical Corp.; Oct, 19, 2006 466,000 syringes | 0.9% Sodium Chloride Flush Syringe, 2.5 mL. Product Code: E0100-30. Manufactured by Excelsior Medical and distributed by Hospira under the label Syrex. | The syringe manufacturer mixed a pre-printed heparin labeled flush syringe with the saline syringes |

Hospitals and other purchasers of IV flush syringes should keep abreast of recalls and avoid manufacturers who’ve had repeated recalls that indicate deficient quality control.

But that’s not always as easy at it might seem, according to the pharmaceutical trade publication Pharmacy Practice News. Companies may changes their names as a result of mergers and acquisitions. And sometimes, the name on the syringe is that of the supplier, not of the company that actually manufactured it.

Nurse Assist Normal Saline IV Flush Syringe and B. Cepacia Bacteria

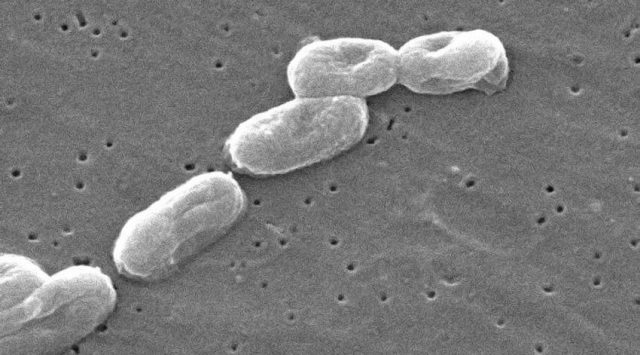

Unfortunately, some of the recalls mentioned above have had grave consequences. The 2016 recall of more than 300,000 normal saline IV flush syringes by Texas-based Nurse Assist led to an outbreak of Burkholderia cepacia infections.

The bacteria, which can be deadly to immunocompromised individuals, were found in the blood of 164 patients in 59 medical facilities in five states. Seven people died but it’s unclear whether those deaths were directly caused by the infections, underlying conditions or something else, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

New Jersey reported the most cases, with 59, followed by New York with 58 and Pennsylvania with 30. The remaining cases were reported in Delaware (4) and Maryland (12).

Fortunately, CDC investigators were able to contain the outbreak after quickly narrowing in on the Nurse Assist syringes as the likely cause of the infections. And a nationwide recall of the devices likely prevented more people from becoming sick.

While it’s still a mystery how the supposedly sterile syringes became contaminated, CDC researcher Dr. Richard B. Brooks told Drugwatch in an email that there are several ways it could have happened.

“It is unlikely that the bacteria would have survived properly conducted sterilization with gamma radiation,” Brooks wrote. “Therefore, the most likely explanations for contamination include: 1) the syringes somehow failed to undergo sterilization; 2) there was a problem with the sterilization process in such a way that sterilization was not effective; or 3) bacteria were somehow introduced into the saline in the syringes after sterilization.”

B. Braun Heparin IV Flush Prefilled Syringe and Serratia Marcescens

Nurse Assist isn’t the only company to come under scrutiny for contaminated syringes.

The federal government brought a case against B. Braun Medical Inc. in 2016 that accused the company of selling contaminated prefilled saline syringes in 2007.

One hundred patients fell ill, some developed serious blood infections and at least five individuals died, according to The Morning Call newspaper. Authorities said the adulterated IV flush syringes infected patients in California, Texas, New York and Nebraska with the bacteria Serratia marcescens.

Among those affected by the contaminated syringes was Kyle Pacheco, a 19-year-old from South Florida who was recovering from a bone marrow transplant. According to ProPublica, Pacheco became so seriously ill from the contaminated syringe that he fell into a month-long coma and could barely walk when he woke up. He passed away in 2010.

$7.8 Million Settlement

A government investigation into the matter revealed that B. Braun wasn’t actually the company that had manufactured the contaminated syringes. Rather, B. Braun was buying its supply of saline flushes from a small North Carolina outfit called AM2PAT Inc. that had a history of deficiencies.

Moreover, B. Braun was aware that AM2PAT had a history of manufacturing problems and had received warning letters from the FDA, but B. Braun chose to buy and resell AM2PAT’s syringes anyway.

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, IV flush syringe manufacturer AM2PAT employed “bad manufacturing processes” that resulted in syringes that were “contaminated with bacteria and dangerous to patients.”

The company’s failures included:

- Failing to clean its manufacturing equipment and factory

- Failing to properly train employees

- Failing to test equipment to ensure it was in working order

- Using “dirty and filthy equipment” to manufacture syringes

AM2PAT eventually fired its entire staff and closed its doors completely. B. Braun agreed in May 2016 to pay $4.8 million in penalties and forfeiture and up to another $3 million in restitution to resolve its criminal liability for selling the contaminated syringes.

Better Tracking Needed

While such outbreaks are very rare, Brooks says they underscore the need for better tracking systems for saline flush syringes and other medical devices.

Currently, there is no good mechanism in place for tracking which individual saline flushes are used on specific patients, and that can make it hard to figure out who’s at risk when a contamination-related outbreak occurs.

“An improved mechanism for tracking flushes and other similar devices might help in more quickly identifying patients who have received a specific product,” Brooks told Drugwatch.

In the meantime, consumers can stay well informed of adverse events associated with medical devices like saline syringes by checking the FDA’s searchable MedWatch website.

“They can also further protect themselves by asking their providers if they are following evidence-based infection control practices, including hand hygiene protocols and safe injection practices,” Brooks said.

Calling this number connects you with a Drugwatch representative. We will direct you to one of our trusted legal partners for a free case review.

Drugwatch's trusted legal partners support the organization's mission to keep people safe from dangerous drugs and medical devices. For more information, visit our partners page.