IVC Filter

An inferior vena cava filter, also known as an IVC filter, is a small, metal device designed to trap large blood clots and prevent them from traveling into the heart and lungs. Using a small incision, doctors use minimally-invasive techniques to implant these devices in the largest vein in the abdomen known as the inferior vena cava.

IVC filters are inserted into the inferior vena cava to help prevent potentially fatal blood clots and pulmonary embolisms in the lungs. The IVC is the main vein that brings oxygen-low blood back to the heart. Doctors commonly place the devices in those who are at risk of pulmonary embolisms when blood thinners are ineffective or not an option.

When blood flows past the IVC filter, the metal wires capture and trap traveling blood clots before they reach the heart and lungs. However, if left in too long, the filters may cause a variety of serious complications.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the device in 1979, and its use has increased continuously through the years. By 2012, doctors had inserted about 259,000 filters in patients, according to a 2016 study in Seminars in Interventional Radiology.

But a 2016 analysis published by the American College of Cardiology found the devices were likely being over-used, retrieval rates were low and surveillance data was lacking. A 2022 report published in the Journal of Vascular Surgery noted that IVC filter complications were between 1.8% and 3.1%.

“In the United States, the IVC filter implantation rates are 25 fold higher than in Europe,” according to Dr. Riyaz Bashir, director of vascular and endovascular medicine at Temple University Hospital. “The hospitals across this country collectively are spending close to a billion dollars on these devices every year without a known significant benefit.”

Retrievable versions of the filters should only be left in for a short time.

“The advent of retrievable filters led to more widespread use because it was thought that they could safely be used as either temporary or permanent device implants. However, this false sense of confidence has actually led to overuse of filters. Even though retrievable filters were also approved for use as permanent devices, it turns out they may not be safe for longterm implantation. To make matters worse, many of these filters become firmly embedded over time making them difficult to safely remove,” Dr. William Kuo, Director of the Stanford IVC Filter Clinic told Drugwatch.

“Historically, most filters implanted in the U.S. have not been adequately followed for removal. By the time the filter has been rediscovered, often years later, the devices have grown into the vein wall making them a challenge to remove safely,” Dr. Kuo said.

In 2010 and again in 2014, the FDA issued safety warnings about IVC filter complications, including device migration, filter fracture, embolization, blood vessel perforation, difficulty removing the device, lower limb deep vein thrombosis and inferior vena cava occlusion.

“The FDA is concerned that retrievable IVC filters, when placed for a short-term risk of pulmonary embolism, are not always removed once the risk subsides.”

The agency recommends doctors consider removing retrievable filters as soon as the risk of pulmonary embolism passes and usually within a 29- to 54-day window. After that time period, potential harm outweighs the likely benefit, according to a 2013 FDA analysis published in the Journal of Vascular Surgery.

“The FDA is concerned that retrievable IVC filters, when placed for a short-term risk of pulmonary embolism, are not always removed once the risk subsides,” the agency said in a 2014 safety communication.

Filter Uses and Types

Blood clots that develop deep inside the pelvis and the lower and upper extremities are referred to as deep vein thrombosis, or DVTs.

DVTs can become life-threatening if they travel to the lungs and cause significant blockage in the lung arteries thereby interfering with oxygenation. This is known as acute pulmonary embolism, or PE. PEs cause about 300,000 deaths every year and they are the third most common cause of cardiovascular death in hospital patients.

People who take blood thinner medications but still experience DVTs and/or people who cannot tolerate blood thinners because of current bleeding or risk of bleeding are candidates for IVC filters. Doctors occasionally recommend the devices prophylactically in patients who are undergoing major surgery if there is a high risk they may develop blood clots.

Historically, two types of IVC filters have been manufactured: permanent and retrievable. Due to the risk of filter-related complications from prolonged implantation, permanent filters have largely been replaced by retrievable-type filters. However, even though retrievable filters were also approved for use as permanent devices, it turns out they may not be safe for longterm implantation either. Therefore, both filter types may cause complications down the road if not monitored closely and promptly removed..

“There are over two dozen filter types that may be encountered in patients residing in the U.S. The spectrum ranges from old, permanent devices inserted decades ago that have now been discontinued all the way to the latest retrievable ones.” Dr. Kuo said.

Some companies that manufacture devices available in the United States are ALN Implants, Argon Medical, B. Braun, BD Interventional (formerly C.R. Bard), Boston Scientific, Cook Medical, Boston Scientific, Cordis J&J, Mermaid Medical.

- The Bard G2 Express filter

- The Bard G2 filter

- The Bard Recovery filter

- The Cook Celect filter

- The Cook Gunther Tulip filter

- The Boston Scientific Greenfield filter

Placement and Removal

Doctors use a catheter to insert the device into a patient’s inferior vena cava through a small incision in either the neck or groin.

The way doctors remove retrievable filters is similar to how they implant them. Health care providers inject contrast or X-ray dye in the vessel containing the device to make sure there are no blood clots in the filter prior to attempting removal. A catheter-like snare is then inserted into the vein and used to engage the retrieval hook located at the end of the filter. A sheath is then inserted over the filter to collapse and remove the filter.

Possible Complications

IVC filters have the potential to migrate away from their implanted location. Sometimes the device components may penetrate through the vein leading to a variety of complications. Broken pieces of filters can travel through the blood and lodge into organs such as the heart.

“Patients should try to identify exactly which device was implanted within them, because some filters have been associated with a higher risk of complications including fractures, penetrations, even blood clots,” Dr. Kuo told Drugwatch. “No device is perfect, and I have actually seen major complications occur from every filter type in existence.”

Complications typically fall into three categories: procedural, delayed and retrieval.

- Access site bleeding and/or bruising

- Incorrect placement and/or malposition of filter

- Defective filter deployment

- Bleeding

- Blood clots

- Difficult retrieval causing long procedure times and excess radiation exposure

- Filter fracture

- Filter component migration into the heart or other organs

- Filter penetration into adjacent organs

- Vessel scarring with risk of blood clots (Deep vein thrombosis)

- Vessel blockage resulting in debilitating pain and leg swelling.

Adverse Event Reports and FDA Actions

Between 2005 and 2010, the FDA received nearly 1,000 adverse event reports involving IVC filters. Most involved device migration and embolization, which is a movement of the entire filter or fracture fragments to the heart or lungs. Seventy cases involved perforation of the vena cava or internal organs, and 56 involved the device breaking.

The agency concluded the complications could have been related to retrievable filters remaining in the body after the risk for pulmonary embolism had subsided. It recommended removing retrievable devices within 1-2 months after implantation, once the filter is no longer needed.

The FDA is also requiring manufacturers to participate in studies that will provide additional information about the safety of permanent and retrievable filters. Manufacturers have been given the option of participating in specific research, known as the PRESERVE study, or various postmarketing surveillance studies.

PRESERVE stands for PREdicting the Safety and Effectiveness of InferioR VEna Cava Filters. The independent national clinical study will examine the safety and effectiveness of using IVC filters to prevent pulmonary embolism. The PRESERVE study is slated for completion in May 2019.

The data gathered from the PRESERVE study and the 522 postmarketing studies will “help the FDA, manufacturers and health care professionals assess the use and safety profile of these devices as well as understand evolving patterns of clinical use of IVC filters, with the goal of ultimately improving IVC filter utilization and patient care,” according to a 2016 study in Seminars in Interventional Radiology.

However, the main limitation with PRESERVE is that the protocol only required a small number of patients per filter type and a short follow-up interval overall. This PRESERVE protocol design was eerily similar to the flawed trials that manufacturers initially used to obtain FDA clearance of these exact filters via the non-rigorous 510K pathway—the same pathway that has allowed approval of many other faulty devices such as nickel-based hip implants.

Manufacturer Recalls

Six major IVC filter recalls between 2005 and 2015 affected more than 81,000 units. Packaging and label issues prompted most of the recalls, according to the manufacturers.

While there have been no major recalls since 2015, thousands of people implanted with the devices have reported complications. And companies have not recalled some of the most problematic devices.

A 2015 NBC News investigation linked Bard Recovery and G2 filters to 39 deaths. The company never recalled either device. Instead, it replaced them with similar models.

Cook Medical filters also face blame for injuries and deaths. The FDA has received hundreds of reports of Cook Celect and Gunther Tulip problems, but the company never issued recalls for either.

Meanwhile, thousands of people who suffered injuries have filed IVC filter lawsuits.

What Studies Say

Research studies have confirmed problems with retrievable IVC filters. A 2013 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association, or JAMA, looked at the devices’ failure rate. Researchers discovered doctors only removed 58 out of 679 retrievable filters. When the filters remained in patients longer than medically necessary, 18.3 percent of attempts to remove the devices failed, 7.8 percent of patients had venous thrombotic events, and 25 patients suffered pulmonary embolisms.

Failure Rates

Introduced in 2003, the Recovery filter was C.R. Bard’s first-generation product. A second-generation device, the Bard G2, arrived in 2005 as a replacement for the Recovery. But before Bard replaced the Recovery, the FDA had received 300 reports of adverse events linked to the device.

Results from one study showed about 25 percent of the Recovery filters failed, causing the device to fracture or break apart. One patient died at home, although the study did not explain the reason. The NBC News investigation linked the device to at least 27 deaths.

The Bard G2 had a 12 percent failure rate and remained on the market a shorter amount of time than its predecessor. Bard stopped selling the Recovery when the G2 arrived on the market in 2005. The G2’s successor, the G2 Express, entered the market in 2008. One study found all of Bard’s devices experienced a combined 12 percent fracture rate.

‘Significant Decline’ in Use Since 2010

A 2017 study found use of IVC filters experienced a “significant decline” after the FDA’s 2010 safety warning.

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis looked at more than 1 million patient records covering a 10-year period. Between 2005 and 2010, use of the device rose by more than 22 percent. But it dropped dramatically after the FDA advisory, falling more than 25 percent by 2014.

At their peak in 2010, nearly 130,000 IVC filters per year were placed in patients. By 2014, the number had dropped to around 96,000, according to the medical textbook, Vascular Medicine: A Companion to Braunwald’s Heart Disease.

Higher Mortality Risk

A study that appeared in JAMA Network Open in 2018 found an association between IVC filters and increased risk of death. The study looked at 126,000 patients’ medical records and found the risk of dying within 30 days of getting a filter shot up 18 percent for certain patients.

Those at risk had two specific conditions: they had venous thromboembolic disease, or VTE, disease and they could not take blood thinners. VTE includes deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism or both.

The researchers called for randomized clinical trials to better test the filters’ safety and effectiveness.

Other Treatment Options

IVC filters should primarily be used in patients with acute blood clots who cannot take blood thinners. If filters are used for any other reason, this should only be done after careful consideration and appropriate documentation, experts say. Otherwise, filters should not be widely used, and most patients with blood clots should simply be treated with blood thinners, close monitoring and lifestyle modifications.

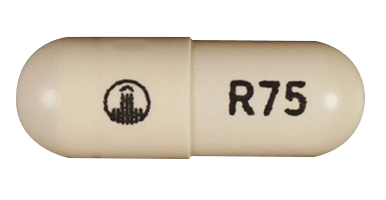

Historically, the most widely used blood thinner was warfarin, but newer anticoagulants like Xarelto, Pradaxa and Eliquis are increasingly being prescribed. All blood thinners are associated with an increased risk for bleeding, so patients should be closely monitored, especially those patients who are prescribed life-long blood thinners.

Calling this number connects you with a Drugwatch representative. We will direct you to one of our trusted legal partners for a free case review.

Drugwatch's trusted legal partners support the organization's mission to keep people safe from dangerous drugs and medical devices. For more information, visit our partners page.