Talcum Powder: The Feminine ‘Hygiene Extra’ That May Have Fueled a Cancer Crisis

For decades, women have been taught to use talcum powder as part of their feminine hygiene routine. Advertising has perpetuated this myth by telling us we need a “sprinkle a day” to feel sexy and smell good. But medical experts say there’s no need for women to use talc in this manner and warn it may raise your risk of cancer.

In a St. Louis courtroom in June 2018, Gail Ingham reflected on her three decades’ use of Johnson’s Baby Powder. The 73-year-old St. Louis native told jurors she had started using the iconic product to stay fresh and dry around 1957 when she turned 13.

“I saw on TV back then a lady holding a small bottle of Johnson & Johnson powder and saying, ‘Use this for your daily hygiene.’ That’s where I saw it and that’s what gave me the idea to use it,” Ingham testified.

She stopped dusting herself with baby powder in 1985 when she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, not realizing at the time that the two might be linked. She was simply following her doctor’s orders not to use anything on her body without his permission.

But following a six-week trial in the summer of 2018, a jury concluded Johnson’s Baby Powder and other talc-based products contained the cancer-causing mineral asbestos and caused Ingham and 21 other women’s ovarian cancer. The jury awarded them $4.69 billion.

The record talc verdict generated international headlines and called attention to the controversy surrounding talcum powder, which some studies have linked to ovarian cancer and mesothelioma.

The stories and testimony of Ingham and other women in the trial, which Drugwatch viewed through archived video footage of the trial on Courtroom View Network, also underscore how entrenched myths about feminine hygiene have led millions of women to use unnecessary and potentially harmful products on their bodies — and how companies like Johnson & Johnson have perpetuated those myths and profited from the phenomenon.

Taboo of Feminine Hygiene

Most of us are familiar with the pleasant scent and silky feel of talcum powder. Since its introduction in the late 1800s, Johnson’s Baby Powder has become inextricably tied to bath time for hundreds of millions of babies and children.

But for some women, puberty ushers in another relationship with talcum powder that is often fueled by shame and fear. Shame that our bodies bleed every month. Fear that you might smell down there. Fear that others will smell you and be disgusted.

“Honestly, I don’t remember a time not using it,” Stephanie Martin, who was diagnosed with ovarian cancer at age 42, told a jury last July. “But I do remember in like the sixth grade when you start your period and you’re just very paranoid that they’re gonna know I’m on my period, so you use a lot of powder because you want to stay fresh — and South Carolina is extremely hot.”

These are the types of fears and insecurities Johnson & Johnson and other companies capitalized on when they aggressively marketed their talc products as a solution to a problem manufactured by societal expectations.

Sprinkle it on your body and talc will soak up any moisture and mask any offending odors, they told consumers. Decades of advertising promised the feminine hygiene practice wouldn’t just keep you fresh and clean, but also it would make you more confident in your job or more desirable to the opposite sex.

Never mind the fact that the vagina doesn’t actually need a “sprinkle a day,” or that it’s a brilliant self-cleaning organ. Dusting our vaginas with baby powder became a grooming ritual as common for many women as brushing one’s teeth or applying deodorant.

Motioning with her hands as if she were shaking an invisible bottle, Martin explained in detail to the St. Louis jury how she’d sprinkle the powder on her hands, rub it under her arms, under her breasts, in her bra and in her genital region.

“I’d bring my underwear to my thighs and shoot it in there, but I didn’t want it clumpy, so I’d kind of shake it and bring it up, and I’d poof it out a bit,” the then-46-year-old South Carolina woman testified.

It’s a habit many of us learned from our mothers, who learned from their mothers, and we never really questioned it — until recently. Until some researchers noticed an increased risk of ovarian cancer among women who used the powder as a feminine hygiene product. Until talcum powder users with ovarian cancer began suing Johnson & Johnson.

Profiting from Unnecessary Products

With its savvy marketing, Johnson & Johnson’s baby powder product line has generated hundreds of millions of dollars for the consumer products and pharmaceutical giant.

A company email from 2008 describes the company’s iconic baby powder as a “$70M business in the U.S. alone.” But Johnson’s Baby Powder isn’t just a cash cow; it’s also been the corporation’s “sacred cow,” according to another internal email cited by Reuters.

Indeed, through the years, the iconic baby powder cemented Johnson & Johnson’s image and reputation as a caring company and brand that mothers and families could trust.

But many consumers, including the women in the St. Louis talc trials, now lament that they had never heard about a possible link between talcum powder and ovarian cancer. And many have been shocked to learn from a bombshell report published by Reuters that Johnson & Johnson had been aware for decades that its talcum powder was sometimes contaminated with asbestos but failed to notify regulators and warn the public.

The investigative report was based on memos and other documents unearthed in recent talc litigation.

- Lab reports as far back as 1957 and 1958 showed talc from Johnson & Johnson's Italian supplier had been contaminated with asbestos.

- Johnson & Johnson’s raw talc and powders continued to test positive on occasion for small amounts of asbestos from 1971 through 2003.

- In the early 1970s, Johnson & Johnson urged the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to adopt a testing method for talc that would have allowed it to contain an asbestos level of up to 1 percent, which was 10 times the allowable amount the FDA had proposed. After the watchdog agency rejected the idea, Johnson & Johnson promoted self-policing by an industry group. To this day, the FDA does not limit asbestos levels in cosmetic talc, and the industry monitors itself.

Johnson & Johnson has rebutted the Reuters report, calling it “one-sided, false and inflammatory.” The company stands by its assertions that its talc products are completely safe and do not cause cancer.

“Decades of independent scientific testing has confirmed that our products are safe and are not contaminated with asbestos,” Johnson & Johnson states on its “Facts About Talc” website. “If we believed our talc was unsafe, it would not be on shelves.”

But the company disclosed in a February 2019 Securities and Exchange Commission filing that the Justice Department and SEC have launched inquiries into the matter and have subpoenaed documents from the consumer products giant.

And the fact remains that talcum powder isn’t essential for a woman’s health and hygiene, according to medical experts.

“[Women] worry about odor, or they worry about moisture or those sorts of things, so they’re trying to clean it or cover it up or when it’s really not necessary,” Sandra Cesario, a professor at the College of Nursing at Texas Woman’s University, told Drugwatch. “Just plain old soap and water and keeping yourself clean is the best way to prevent all kinds of infections and other issues.”

‘Plus-Sized Southerners’ and Other Targets

Martin, meanwhile, was precisely the sort of consumer Johnson & Johnson enticed to buy its talc products.

An internal marketing document from 2010 outlined how the company hoped to increase sales by targeting “overweight women living in hot climates during key summer season.” The company even had a special name for its target demographic: “plus-sized Southerners.”

Other internal company documents that have emerged from litigation show how Johnson & Johnson also targeted Hispanic and African-American women and teenage girls to try to boost sluggish baby powder sales and promote talc as an essential feminine hygiene product.

A 1992 marketing memo suggested investigating “ethnic (African American, Hispanic) opportunities to grow the franchise.” The same memo identified “negative publicity from the health community on talc (inhalation, dust, negative doctor endorsement, cancer linkage)” as a major obstacle.

“The brand will institute an adult Hispanic media program and potentially launch an adult Black print effort,” the memo stated.

Another marketing proposal boasted about two “high-scoring ads” Johnson & Johnson planned to run in Seventeen and other teen magazines to capture more teenage girls as customers. One of the ads featured an attractive teenage girl cradling her boyfriend’s head in her lap and the phrase “You Start Being Sexy When You Stop Trying.”

Tying talcum powder to a woman’s sex appeal became a recurring theme. For instance, one 1980s print ad encouraged women to use Johnson’s Baby Powder “For Older Reasons.”

The ad featured a photo of a man nuzzling up to a woman as she cradled his face with her hand.

“Pure JOHNSON’S Baby Powder helps you feel good about yourself by keeping you feeling soft, and smelling clean,” the ad stated. “It helps that come across to other people too, because it helps bring out your best.”

“The softness is for you. The silkiness is for him,” the ad concluded.

A Reinforcing Jingle

Out of all of Johnson & Johnson’s talcum powder advertisements, it was the company’s Shower to Shower ads with their catchy jingle that people seem to remember most.

In one Shower to Shower commercial from 1974, a fortune teller sits with a young woman as they look into a crystal ball. “I see a naked lady,” the fortune teller says as an image of a young woman singing “a sprinkle a day helps keep the odor away” appears in her crystal ball.

“That’s me,” the young woman responds, “but I don’t sprinkle.”

“I know, I know,” the fortune teller laments, holding her hands to her temples. A man then appears in the fortune teller’s crystal ball. “How do I meet him?” the young lady asks. “Sprinkle, sprinkle,” the fortune teller replies.

Many versions of the “sprinkle a day” ad aired, but the message was generally the same: if you want to stay fresh and dry and have social success, use Shower to Shower every day.

Although Johnson & Johnson sold its Shower to Shower product line to Valeant Pharmaceuticals in 2012, the memorable ads still strike a chord among women who used the product.

“Do I specifically remember any [ads]? Not really, but I remember that jingle,” Karen Hawk testified in court in June 2018.

The 67-year-old ovarian cancer survivor recalled using Johnson’s Baby Powder all over her body every day, “sometimes more than once a day.” Like millions of other mothers, she also used it on her children. Listening to her lawyer sing the jingle in a courtroom last year reduced Hawk to tears. “Yes, yes, I do remember that,” she said, dabbing her eyes with a tissue.

“Do I specifically remember any [ads]? Not really, but I remember that jingle.”

Carole Williams, another plaintiff in the 2018 St. Louis trial, was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2011. She also remembered the ditty.

“That one I knew because every time in the morning, ‘I’m having my sprinkle today.’ Just an automatic thought that they embedded in your head with that commercial. Cute little song,” she recalled on the witness stand.

Williams, who was 63 when she testified, said she had been instructed at a young age to use baby powder as part of her daily hygiene routine.

“As soon as I was old enough to bathe myself, we were always taught to use our powder,”she testified. “I don’t know that my brothers did. All my sisters and I did.”

Research Sparks Concerns, Debate

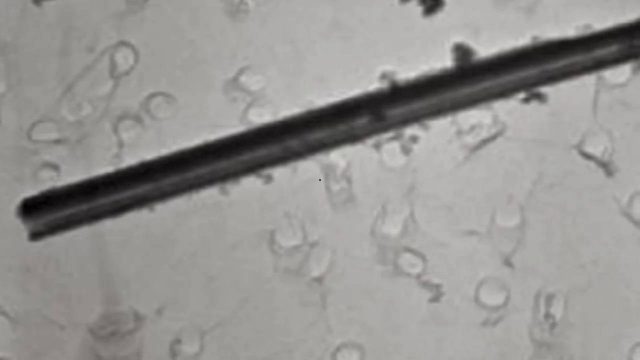

A group of Welsh doctors were the first to note a possible link between talcum powder and ovarian cancer. In their 1971 study, the physicians reported finding talc particles deeply embedded in the tumors of women with ovarian and cervical cancer.

The authors conceded that it was “impossible to incriminate talc” as the cause of women’s cancer based just on their findings. But they said talc might be related to other factors associated with cancer development and called for further investigations.

While the study prompted more research on the topic, as the authors had hoped, it also sparked a contentious debate over the safety of cosmetic talc that has raged on for almost half a century.

Harmless Habit or Cancer Precursor?

In 1982, Dr. Daniel Cramer, a Harvard University researcher, co-authored the first epidemiologic study to show a significant link between talc use and ovarian cancer.

Cramer found about 43 percent of 215 women with ovarian cancer regularly used talcum powder on their genitals, panties or sanitary napkins. By comparison, only 28 percent of 215 women who did not have ovarian cancer used talc for feminine hygiene purposes.

After Cramer’s study was published, Dr. Bruce Semple of Johnson & Johnson asked to meet with him.

“My recollection of this meeting was that Dr. Semple spent his time trying to convince me that talc use was a harmless habit, while I spent my time trying to persuade him to consider the possibility that my study could be correct,” Cramer recalled in court documents.

Cramer suggested to Semple that Johnson & Johnson should warn women about the potential risks.

“I don’t recall further meetings or communications with him,” Cramer stated.

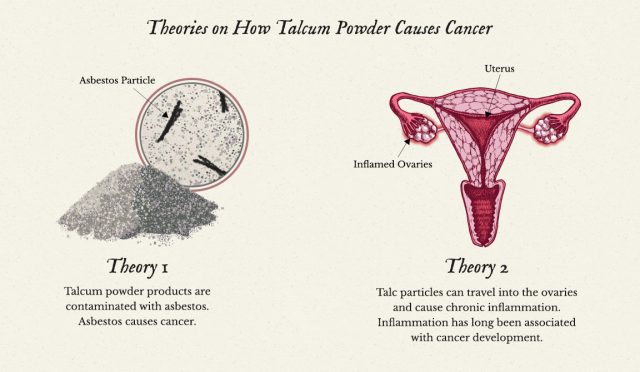

Theories on Talc-Cancer Connection

In an interview with Drugwatch, Cramer explained his theory of how he believes talcum powder may cause ovarian cancer.

“If it’s used near the vaginal area, it will get into the vagina, and it will get up into the pelvic cavity,” explained Cramer, who has served as an expert witness for plaintiffs in several talcum powder lawsuits. “It does migrate from the low to the upper genital tract.”

Once it migrates, Cramer theorizes, the talc sets off an inflammatory response that can damage the DNA of surrounding tissues and cause cells to turn cancerous.

Another hypothesis is that talcum powder products are inadvertently contaminated with asbestos when they’re mined from the earth. Asbestos is a known carcinogen and the primary cause of mesothelioma, a lethal cancer that primarily affects the linings of the chest and abdomen. Some believe it may trigger ovarian cancer in the same way.

“There have been some good animal studies which show [talc] does induce inflammatory lesions of the female tract and it does induce papillary growth on the ovary, very similar to those induced by asbestos instilled into a pelvic cavity,” Cramer said. “We are trying to resume those studies.”

Study Evidence Mixed

Not all studies have demonstrated a link between talc use and ovarian cancer — a point that Johnson & Johnson has played up in the media and in the courtroom.

As of 2022, the company also points out on its website that “a statistical association between ovarian cancer and powder users is not found in large, prospective studies, although some, but not all, case-control studies do indicate a slight statistical association.”

The difference is important, Johnson & Johnson argues, because case-control studies identify individuals with a particular disease history and ask them about possible risk factors. And such studies may encourage a phenomenon known as “recall bias,” which is when an individual with a disease overestimates their exposure to risk factors.

Nonetheless, more studies than not show a connection, according to a 2018 analysis of talc safety prepared by the government of Canada.

Fifteen epidemiological studies published between 1989 and 2016 showed a positive association between perineal talc use and ovarian cancer, and six studies showed a “possible” connection. Only nine studies showed “no association,” according to the Canadian report.

Searching For Answers

Cesario, an expert on ovarian cancer, said she decided to delve into the issue after doctors diagnosed her daughter with ovarian cancer in 2003.

Anna was just 23 when she found out she had stage 4 ovarian cancer, Cesario said, and there was no known history of the disease in their family. Anna died in 2009.

“She was a healthy, average-weight, didn’t drink, walked everywhere, healthy sort of college student,” Cesario told Drugwatch.

As Cesario began looking at possible ovarian cancer risk factors and triggers, she reflected on her daughter’s use of talcum powder.

“She was a dancer and all of the dancers used talc or baby powder, mainly because they don’t wear underwear [so they use it] to absorb moisture and reduce chaffing because of the active movement,” Cesario explained. “So dancers do use it a lot … I can’t say that that’s what caused it, but it fits the profile.”

Cesario ended up surveying nearly 1,300 women, including 553 women with ovarian cancer, and asked them about their use of genital talc, tampons and douching.

More than 54 percent of the women who reported using talcum powder on their genitals reported having ovarian cancer. About 40 percent of the women who reported using talcum powder on their genitals said they did not have cancer.

“My study did show that women who did use talcum powder were at a higher risk for ovarian cancer,” Cesario said.

“My study did show that women who did use talcum powder were at a higher risk for ovarian cancer.”

Cesario also looked at tampon use and douching.

“[With] tampon use there was nothing different in the groups, but with douching there was. If they used a combination of douching and talcum powder, it was an even higher risk,” Cesario said. “I think that’s significant.”

Cesario said she doesn’t believe talcum powder alone causes cancer, but it’s just “one more thing to increase your risk.”

Cancer development, Cesario explained, is usually a multi-factorial process. A family history of ovarian cancer, inherited gene mutations and early menstruation, for example, can all increase a woman’s risk of developing ovarian cancer.

“I don’t think there’s one single causative agent. I think it’s a combination of things. It’s a multi-factorial sort of process,” she said. “What if you’re of Jewish descent and a BRCA [gene] carrier? And you have all of those things and you use talcum powder and you’re obese and your mother had breast cancer — all those things go together.”

At the end of the day, though, Cesario said she believes women should avoid using talcum powder near their vaginas.

“Now that we have the evidence, or a growing body of evidence, I would recommend to not do it,” Cesario said. “Even though it’s not a real strong link … if you don’t need it, don’t use it.”

‘Fingerprints’ Point to Potential Cancer Culprit

It’s a warning the 22 women involved in the St. Louis trial wish they had heard.

“I used a product that I believed was safe, and not just for me to use but to use on my children, on my great nephew, on my niece. And I just want to keep other women from getting this, from this happening to them,” Andrea Schwartz-Thomas said in a taped deposition played at the trial.

Schwartz-Thomas began using Johnson’s Baby Powder when she started lifeguarding at the age of 15, and she used it on a daily basis for nearly 30 years.

She passed away on Aug. 15, 2018 at the age of 48, four years after being diagnosed with stage 4 ovarian cancer and about one month after a jury awarded her and 21 other plaintiffs (including six who were deceased) $550 million in actual damages and $4.14 billion in punitive damages.

To arrive at the punitive damages, the jury multiplied Johnson & Johnson’s $70 million in annual baby powder sales by the 45 years that had elapsed since the company claimed its product was asbestos-free. They then multiplied $22 million, or $1 million per plaintiff, by 45 years and added that figure to the total.

“We were just trying to find something [the company] would feel,” an unidentified juror told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Some of the most riveting testimony in the trial, meanwhile, came from Dr. Mark Rigler, a microbiologist and chemist with expertise in forensic science.

At the request of plaintiffs’ attorneys, Rigler examined tissues from the tumors of a number of plaintiffs in the case. He found particles of either asbestos or talc in the tissue of 10 of them — results the plaintiffs’ lawyer called “the fingerprints” in the case.

Schwartz-Thomas’ right ovary tested positive for ferro-anthophyllite, a type of asbestos that some testing has also found in Johnson’s Baby Powder. Rigler found tremolite, another type of asbestos, in the ovaries, lymph nodes and/or fallopian tube tissue of five other women.

In Williams’ right ovary, Rigler found actual talc particles. The finding surprised him.

“I didn’t expect to find it at all,” he testified. “The body tries to reject and get rid of this material.”

The FDA’s Role in Protecting Consumers

The government of Canada is considering restricting the use of talcum powder and warning consumers about a “causal effect” between perineal talc use and ovarian cancer.

Even Sri Lanka is taking a hard look at Johnson’s Baby Powder, according to Reuters. In January 2019, the Sri Lankan government halted imports of the product and said it will not resume imports until J&J India provides new test results that show the powder is asbestos-free.

Government regulators in India and Bangladesh are also collecting and testing Johnson’s Baby Powder to look for asbestos in the product, according to Reuters.

Meanwhile, the United States government has taken a mostly hands-off approach to talc.

On its website, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration states it “continues to investigate and monitor reports of asbestos contamination in certain cosmetic products.” But the agency also notes cosmetic products “do not have to undergo FDA review or approval before they go to market.”

Instead, the cosmetics industry essentially regulates itself through the Cosmetic Ingredient Review (CIR) panel, an industry-led group. Not surprisingly, the CIR rejects the notion that talc particles can travel up a woman’s genital track to ovaries. The group insists talcum powder is safe and does not cause ovarian cancer.

When the FDA tried to conduct its own analysis of talc safety in 2009 and 2010, the agency’s efforts fell short. Only four of nine talc suppliers complied with the FDA’s request for samples of their raw talc. In addition to those four samples, the FDA also tested 34 various cosmetic products purchased from Washington, D.C. retail stores.

The agency did not find asbestos in the samples it tested, but it noted the results were “limited.”

“[T]hey do not prove that most or all talc or talc-containing cosmetic products currently marketed in the United States are likely to be free of asbestos contamination,” the agency said.

Experts who’ve examined talc for plaintiffs in talc lawsuits have identified asbestos in talc products.

Dr. William Longo, a world renowned expert in identifying asbestos, tested “100 times more J&J talcum powder” in two years than Johnson & Johnson tested in 50 years, according to a plaintiff’s lawyer. He ended up finding asbestos in more than half the bottles he tested.

In response to Reuters’ explosive reporting, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb promised the FDA would host a public forum in 2019 to examine the development of “standards for evaluating any potential risk” associated with talc cosmetics.

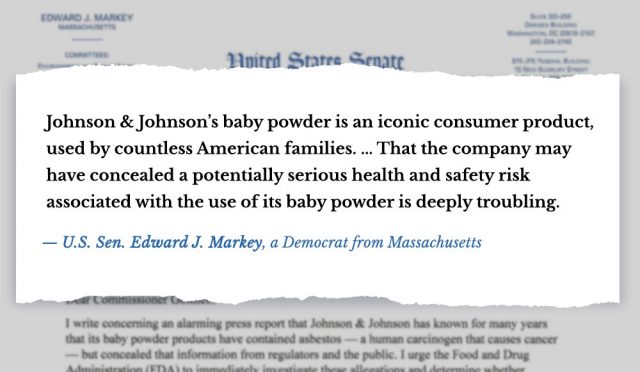

But some members of Congress have called that response inadequate.

In a Dec. 14, 2018 letter to Gottlieb, Democratic Sen. Edward Markey of Massachusetts urged the watchdog agency to “begin looking into this matter immediately, using the full force of its regulatory and investigatory authority.”

“The FDA must determine whether Johnson & Johnson misled regulators and whether its baby powder products have posed, and continue to pose, a threat to public health and safety, and if so, take all appropriate steps in response,” Markey wrote.

Democratic Sen. Patty Murray of Washington, meanwhile, has requested documents and information from Johnson & Johnson related to its safety record. She told the company’s CEO she wants to know more about the steps the company took to determine whether its baby powder contained possible carcinogens and how the company presented that information to regulators and the public.

“I am troubled by recent reports of an alleged decades-long effort by Johnson & Johnson to potentially mislead regulators and consumers about the safety of one of its products, which may have resulted in long-term harm for men, women, and children who used Johnson & Johnson baby powder,” Murray wrote in a Jan. 29 letter to Johnson & Johnson CEO Alex Gorsky.

Murray is the highest ranking Democrat on the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor & Pensions (HELP).

Changing the Conversation

In the meantime, groups such as Women’s Voices for the Earth are trying to get the word out to consumers about the potential dangers associated with non-essential feminine care products, such as talc-based powders.

Alexandra Scranton, the director of science and research for the Montana-based non-profit, told Drugwatch her group started looking into feminine-care products several years ago “because these were products pretty much predominantly marketed towards women, used by women and because they have such a unique route of exposure, largely vaginal exposure.”

While the FDA regulates tampons and pads as medical devices, and most women who menstruate consider them a necessity, a huge number of other products including douches, wipes and powders have little federal oversight and are used as a matter of personal preference, Scranton said.

“Talc and the perineal dusting of talc … kind of fits right into that. It’s been marketed for many years as kind of a ‘hygiene extra,’ and in this case, there has actually been some research showing this exposure very well might be dangerous in increasing the risk of ovarian cancer specifically,” she explained.

“There are a lot of cultural norms that have been created over the years. There's a huge variety of reasons behind them, but certainly the marketing of these products has encouraged that [you’re] dirty or not a proper woman or you won’t have the confidence to do your job if you don’t use these products.”

Women’s Voices encourages women to have “Detox the Box” parties, where they can learn more about the chemicals in period and personal care products and share information about safer alternatives.

The group also encourages women to write to their local newspapers to get their community talking about ingredient safety and the body-shaming marketing messages that companies use to sell wipes, washes, powders, douches and other products.

“There are a lot of cultural norms that have been created over the years,” Scranton said. “There’s a huge variety of reasons behind them, but certainly the marketing of these products has encouraged that [you’re] dirty or not a proper woman or you won’t have the confidence to do your job if you don’t use these products.”

Scranton is optimistic the group’s efforts are helping to change the conversation about women’s bodies and how we treat them.

“A lot of women have used these products for years and years without thinking about what effect it will have on their life and maybe they’re thinking, ‘Wait a second, that is a very special part of my body and what am I putting on this and what is it doing?’”

And Scranton believes that sort of self-awareness can eventually influence the actions of corporate America.

“I think that awareness is starting to get customers asking questions and companies are getting questions to their 1-800 consumer lines and things like that,” she said. “That kind of motion is in place and that’s going to affect companies for sure when they have to start answering hard questions.”

Giant verdicts, though, may be the biggest wake-up call for such companies, Scranton said.

“Certainly with talc, what’s got the attention of other companies I’m sure are the enormous lawsuit judgments,” she said. “Suddenly this is a very real, expensive liability.”

Calling this number connects you with a Drugwatch representative. We will direct you to one of our trusted legal partners for a free case review.

Drugwatch's trusted legal partners support the organization's mission to keep people safe from dangerous drugs and medical devices. For more information, visit our partners page.