The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is supposed to protect Americans from harmful drugs. But in reality, FDA-approval does not guarantee safety. Critics say Big Pharma funds FDA reviews of new drugs, creating a conflict of interest. The agency is too focused on approving drugs to appease Big Pharma and it lacks the proper authority and funding to protect the public.

Editors carefully fact-check all Drugwatch content for accuracy and quality.

Drugwatch has a stringent fact-checking process. It starts with our strict sourcing guidelines.

We only gather information from credible sources. This includes peer-reviewed medical journals, reputable media outlets, government reports, court records and interviews with qualified experts.

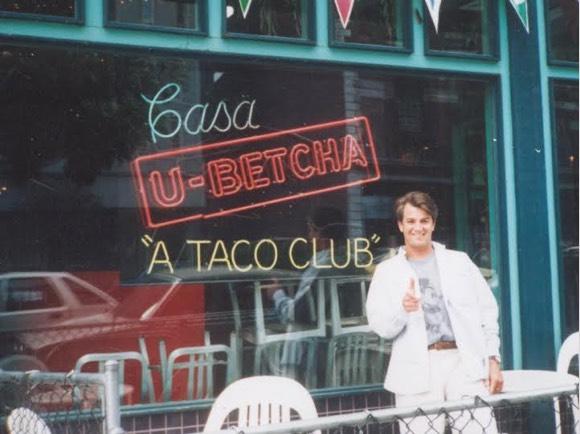

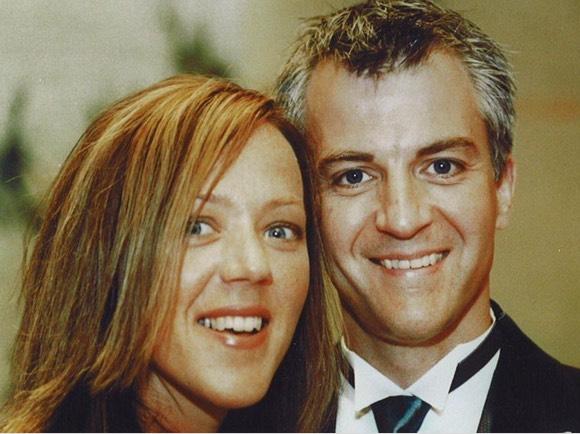

When 37-year-old Timothy “Woody” Witczak’s doctor gave him a few Zoloft (sertraline) samples to help him sleep in 2003, neither he nor his wife, Kim, was alarmed.

“Woody and I never once questioned the drug. Why would we? Zoloft is FDA-approved, given to him by his doctor, and advertised and sold as safe and effective,” Kim told Drugwatch.

A couple of days later, Woody started experiencing side effects including diarrhea, night sweats, trembling hands, nightmares and worsening anxiety. Woody became highly agitated and irritable. His insomnia worsened. He described feeling like his head was outside his body.

Once again, the couple sought the help of their doctor.

“He told us that we should give [Zoloft] four to six weeks to start working,” Kim said.

Five weeks later, Woody — a happily married, energetic, compassionate and cheerful man with a successful career — was dead. He had hung himself in the garage.

“We were shocked at the suicide,” Kim said. “He had no history of depression or mental illness. That night my brother-in-law went home and Googled Zoloft and suicide. He was shocked to learn that the FDA had hearings on Prozac and suicide back in 1991. He told me, ‘I think I know what killed Woody.’”

The family discovered Zoloft, an FDA-approved antidepressant, led to Woody’s tragic death.

Unfortunately, what Woody’s family didn’t know is the FDA’s approval process may favor drug companies over consumers — and FDA-approval does not guarantee safety. In fact, Big Pharma actually pays for the majority of drug safety reviews, provides the FDA with safety data for the review and has the option to have drugs approved faster with fewer clinical trials.

The Birth of a New Drug

“FDA approval is based on evidence — provided by the company that makes the medical product — that the benefits of the product outweigh the risks for most patients for a specific use. It doesn’t necessarily mean the product is safe.”

A new drug takes several steps before it makes its way into a consumer’s medicine cabinet. Unlike medical devices that are cleared for sale without extensive testing if a similar device is already on the market, drugs must go through clinical trials before they are available to consumers.

While the process of approving a new drug may seem thorough on paper, critics say it assumes the world is a perfectly controlled environment. Also, clinical trials have short timeframes and can’t thoroughly determine safety.

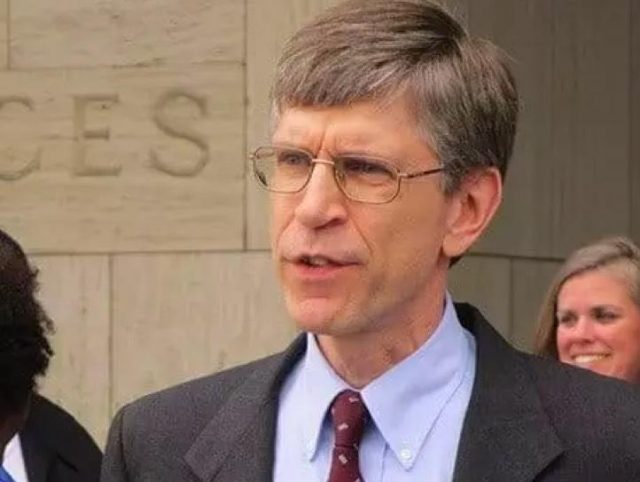

“When a new drug is first approved by the FDA, it typically has only been tested in several hundred to a few thousands patients in carefully controlled clinical trials that last several weeks to several months and that exclude many types of patients who will end up being prescribed the drug,” Michael A. Carome, Public Citizen’s Health Research Group director, told Drugwatch. “As a result, only the most common types of serious adverse events will be detected prior to FDA approval.”

In fact, the FDA calls drug approval a “balancing act” between acceptable risks and benefits on its website. But did Woody Witczak and his family know about this balancing act before he took Zoloft?

“No cautionary warning was given to him or me,” Kim Witczak said. “In fact, the 3-week Pfizer-supplied sample pack that Woody came home with automatically doubled the dose unbeknownst to him from 25 to 50 mgs after week one.”

Essentially, consumers like Woody Witczak and his family are playing the odds when they take a new drug.

“Even though data from human trials are analyzed by a team of experts before a drug is approved, it can be impossible to anticipate all bad reactions — especially very rare safety risks — unless they had also happened with use of a similar drug,” the agency admitted on its website.

The entity responsible for reviewing news drugs is the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). The CDER breaks down the process into phases: preclinical, clinical, and New Drug Application (NDA) review.

1. Pre-Clinical

After a drug company discovers a new compound, it starts the FDA-approval process. The preclinical phase is the drug maker’s discovery and screening phase.

First, it must test the drug on animals to determine its toxicity level. Researchers find out basic safety and efficacy information about the new drug. After it gathers initial data, the drug company submits an Investigational New Drug (IND) application to the FDA. The IND includes basic facts about the drug and a plan for human testing.

After the FDA verifies the planned clinical trials will not put human subjects at unreasonable risk, it moves the drug to the next phase.

2. Clinical Study Phase

The clinical study phase is when the drug maker conducts tests on human subjects. Clinical trials go through three phases.

- Phase 1

- The goal of this phase is to discover what the drug’s most frequent side effects are. Usually about 20 to 80 participants enroll in this phase.

- Phase 2

- The goal of this phase is to discover the drug’s effectiveness. Researchers gather preliminary data on how the drug works in people with a certain disease or condition. Researchers compare the drug against placebo or another drug. Short-term side effects are studied. Usually a few hundred people participate in Phase 2 studies.

- Phase 3

- Phase 3 continues to test safety and efficacy in a larger number of people on different doses and in combination with a few drugs. More than 1,000 patients typically participate in Phase 3 trials.

3. New Drug Application (NDA) Review

Once clinical trials are finished, the drug company submits a New Drug Application. Then, the drug company submits an official NDA that includes animal and human data plus information on how the drug will be manufactured.

The FDA has 60 days to review the NDA before officially filing it. After the FDA files the NDA, it reviews all the research submitted by the drug company for safety and effectiveness. Next, it reviews the drug’s proposed label to ensure health care professionals and consumers get the right information. Finally, the FDA inspects the facility where the drug company will manufacture the drug.

Now, the FDA has the information it needs to decide whether to approve a drug or issue a rejection letter.

New Drug Research and Development Cost and Controversy

The amount a drug company spends to get a new drug on the market is a constant source of debate. Industry claims it is in the billions. It frequently uses this number to justify charging Americans higher drug prices.

In 2011, Donald W. Light and Rebecca Warburton challenged that figure.

Light is a professor of comparative health care policy at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey and a founding fellow of the Center for Bioethics at the University of Pennsylvania, and Warburton is a professor of health economics at the University of Victoria in Canada.

According to Light and Warburton, $56 million is the net cost to companies after taxpayers cover 50 percent of research and development expenses for each new drug they develop. They say drug companies get a large portion of costs paid back from write-offs, National Institutes of Health grants and other forms of creative accounting.

Fast Track to Adverse Events

“For some drugs, safety concerns are only discovered after they have been on the market, sometimes for several years. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has adopted several policies that could increase the likelihood of approving a potentially unsafe medication.”

Big Pharma is fond of criticizing the FDA for not approving drugs quickly enough and depriving patients of life-saving medications. In reality, the FDA approves drugs faster than its counterparts in Europe, Canada and Japan. In the 1980s and 1990s, the FDA began new programs that fast-tracked the approval of certain drugs.

While this might mean some patients benefit from new therapies, the speed at which the FDA approves drugs can have dangerous consequences.

In Witczak’s case, no one told the family that FDA reviewers were pressured to speed up the Zoloft’s approval in the 90s or that the drug’s clinical trial data was questionable.

Dr. Paul Leber, then director of FDA’s Division of Neuropharmacological Drug Products, knew there were problems with Zoloft’s efficacy data in 1991. But he “assured Pfizer that he thought he could convince the Committee that the studies were sufficient to recommend approval,” according to legal documents that surfaced in 2013.

Each year, more than 2 million Americans suffer serious adverse reactions from FDA-approved drugs like Zoloft. These side effects lead to about 100,000 deaths, according to a 2016 study published in The International Journal of Health Services by Sonali Saluja and colleagues.

“This problem is serious. The study by Saluja et al. shows that over 100 million prescriptions were issued for drugs that had to be withdrawn from the market because they proved to be unsafe,” Dr. Don McCanne wrote in response to the study on Physicians for a National Health Program. “This is particularly tragic when it is a drug that never should have been on the market in the first place.”

Study authors found that many safety problems only emerge after the FDA approves drugs and blamed the problems on fast-track drug approval programs.

“Indeed, in the first 16 years after approval, 27 market withdrawals and serious new safety warnings — so-called black box warnings (BBWs) — are issued for every 100 newly introduced drugs,” Saluja and colleagues wrote.

In Europe, regulatory agencies require more review processes for safety and efficacy before insurance plans will even pay for the drugs.

Accelerated Approval and Fast Track Programs

During the NDA Review process, drug companies may apply for Accelerated Approval or a Fast Track program.

-

Accelerated Approval

allows earlier approval of drugs that fill an unmet medical need and uses “surrogate endpoints” to determine effectiveness. A surrogate endpoint is an indicator (for example, blood tests, X-rays) used to tell if a treatment works but does not necessarily guarantee it works. For example, if a cancer drug seems to make a tumor smaller, the FDA concludes it is effective even if there is no clinical trial to prove the drug actually extends life expectancy.

-

The Fast Track Program

reduces approval time for drugs that treat serious or life-threatening diseases. Drugmakers can submit portions of the application instead of providing the information all at once.

Newer and Faster Does not Always Equal Better

Not only are these new drugs risky, most are also no better than previous drugs, according to Donald W. Light and researchers at the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics at Harvard University.

“Public, independent advisory teams of physicians and pharmacists in several countries found over 90 percent of new drugs approved by the FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) offer few or no advantages over existing drugs to offset their risks of serious harm,” Light wrote about the findings in a 2015 post on Health Affairs Blog.

Holes in the FDA-approval Process

“The FDA is supposedly a watchdog agency mandated to protect the public from dangerous and ineffective drugs. In fact, the FDA is ineffective and dangerous to the public.”

While fast-track programs may compromise safety, the FDA’s regular approval process is also not without its own issues. For instance, clinical trials the agency uses to determine safety and efficacy also have several limitations, according to Consumer Reports.

According to a 2003 survey quoted by Consumer Reports, FDA reviewers felt rushed and pressured to approve medications. There are also some studies that found the faster a drug was reviewed, the greater the chance for adverse events surfacing after the drug hits the market.

Mary K. Olson of Tulane University conducted one study in 2003.

- An 18 percent increase of serious adverse reactions

- An 11 percent increase of drug-related hospitalizations

- A 7.2 percent increase of drug-related deaths

The FDA doesn’t always apply the same criteria to all drugs, either. For instance, a study published in JAMA in 2014 by Nicholas S. Downing and colleagues of Yale University School of Medicine found:

- 37 percent of approved drugs were only backed by a single study

- 45 percent of all drugs were approved on “surrogate endpoints”

- 68 percent compared new drugs only to placebos, which this means they determined something was better than nothing — not that the drug was better than another drug

“We’re talking about families going into debt so their loved one can get access to a medication,” Joseph Ross, one of the study authors, told USA Today. “Maybe if they know that a drug doesn’t prolong life, they will be less likely to mortgage their home. People should have access to the full spectrum of information.”

Consumer Reports Issues with FDA Approvals

In 2015, Consumer Reports detailed several issues with the FDA’s pre and post approval processes.

Preapproval issues with FDA drug reviews:

- Clinical trials are too small to give a proper estimation of adverse events.

- Trials only last for a few months, but some dangerous adverse events occur after several years.

- Most trials use specially selected, healthy participants to show that the drug works, but this doesn’t reflect its use in the real world in a bigger, sicker population.

- Doctors may prescribe the drug for off-label uses — uses not studied or approved by the FDA.

- Surrogate endpoints provide a misleading picture of how a drug works.

Post-Approval issues with FDA drug reviews:

- Adverse events are not always reported because reporting is voluntary.

- The FDA may request post-marketing studies to follow up on safety concerns, but drug makers don’t always do them.

- Drugmakers don’t always publish clinical trials with unfavorable results. For example, Merck only published studies showing Vioxx (rofecoxib) patients tolerated the drug well. Several years later it revealed data showing people were having heart attacks.

- The U.S. has no system to regularly scan and analyze large databases of patients for adverse events.

Does the FDA Work for Big Pharma?

“User fees fundamentally changed the relationship between the FDA and the pharmaceutical industry such that the agency now views industry as a partner and a client, rather than a regulated entity.”

While taxpayers still provide about one third of the FDA’s funding, the agency receives the majority of its drug-review funding from Big Pharma — the very industry it should be regulating. It’s a little-known fact to most Americans, and it raises red flags for a number of consumer groups.

“Taxpayers are also paying for agency [funding], but we’re not treated as the customers — the companies are,” Zuckerman said.

Under the Prescription Drug Use Fee Act (PDUFA) of 1992, drug companies pay user fees to get drugs approved. Initially, Congress passed PDUFA to provide a budget to hire more medical scientists and researchers to deal with the drug application load.

Over time, the law expanded. Since 1992, several reauthorizations of PDUFA further weakened the standards for approving drugs. For example, it allowed companies to use one trial instead of two to approve a drug in some cases.

The fact that Big Pharma pays a substantial amount of FDA’s operating costs should give anyone pause, according to critics. This is a big conflict of interest.

“Approximately two-thirds of the agency’s budget for review of drug products is now funded by the pharmaceutical industry,” Carome said. “As a result, speed of review and approval too often take precedence over protecting public health and ensuring that drugs are safe and effective.”

With Big Pharma footing the bill, monitoring side effects may be lower in importance than approving drugs. Professor Donald W. Light estimates the FDA — an institution developed to protect the public from unsafe and ineffective drugs — only spends about 10 percent of its budget monitoring harmful side effects.

Under the White House’s proposed 2018 budget, user fees will grow more than double. This could potentially hike up the influence drug companies already have. The government also plans to decrease federal funding of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services — the FDA’s parent agency, according to the budget outline.

This could potentially make the FDA more dependent on drug companies for funding.

FDA Does Not Conduct Its Own Studies

“All of this is going on behind the scenes while the average, every day person like Woody goes in to their doctor and puts their faith and trust in their doctor. They trust that they are being given a drug, device, or treatment that is ‘safe and effective’ which has been approved by the FDA.”

Another fact that Americans should know is that the FDA does not conduct its own independent studies on drug safety and effectiveness when approving drugs. It relies on data and studies provided by the manufacturers.

This means the FDA can only base its approval or denial on the information the drug company provides, and drug companies may cherry-pick the data they want the FDA to see, according to Dr. Alexander Bingham.

Bingham is a clinical psychologist at Full Spectrum Progressive Psychology and teaches psychological research methods and phenomenological research at John F. Kennedy University in San Jose, California. He did graduate research on the approval of Prozac and says the drug’s approval process is a prime example of manipulating studies.

“Eli Lilly Pharmaceuticals conducted 20 studies to prove the antidepressant effect of fluoxetine hydrochloride, more popularly known as Prozac. Only three studies were ever submitted to the FDA for approval due to 17 outright failures.”

“By its own report, the FDA challenged the validity of all three studies citing both procedural and statistic errors and denied Lilly approval for Prozac twice,” Bingham told Drugwatch.com.

After Lilly sent in a third data submission, the FDA finally approved the drug. But, there were no new trials, “only statistical manipulation and repackaging of existing data to create more favorable results,” Bingham said.

In order to obtain this information, Bingham had to request copies of documents through the Freedom of Information Act. Even then, most of the information was blacked out when he received it.

Manipulating study data is more prevalent than the public knows.

Research fellows at the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics at Harvard University, including Donald W. Light, investigated institutional corruption in the pharmaceutical industry. They found pharmaceutical companies use legal ways to manipulate “FDA rules to generate evidence that their new drugs are more effective and less harmful than unbiased studies would show.”

Drug companies hire a team of writers, statisticians and editors to “repackage” trial results to be favorable to their drugs. Whether the FDA acknowledges this practice and allows it is anybody’s guess.

After Woody’s death, Kim Witczak saw the flaws and corruption in the system firsthand.

“All of this is going on behind the scenes while the average, every day person like Woody goes in to their doctor and puts their faith and trust in their doctor,” she said. “They trust that they are being given a drug, device, or treatment that is ‘safe and effective’ which has been approved by the FDA.”

Risky FDA-approved Drugs Lead to Recalls

“This problem is serious. The study by Saluja et al. shows that over 100 million prescriptions were issued for drugs that had to be withdrawn from the market because they proved to be unsafe.”

History shows a number of FDA-approved drugs that went on to cause serious adverse events. Many patients were unaware that there was even a risk. Later the FDA announced recalls for these products.

According to Saluja and colleagues’ 2016 study, the median time from FDA approval to removal from the market is five years. But some are on the market for decades before removal, placing several million people at risk.

Some Notable FDA-Approved Drugs Later Recalled for Safety Risks Include:

-

ACCUTANE (ISOTRETINOIN)Treats acne. Approved in 1982. Roche officially discontinued the drug in 2009 citing poor sales, but the drug has been linked to birth defects, bowel disease and suicidal tendencies.

ACCUTANE (ISOTRETINOIN)Treats acne. Approved in 1982. Roche officially discontinued the drug in 2009 citing poor sales, but the drug has been linked to birth defects, bowel disease and suicidal tendencies. -

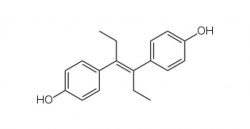

DES (DIETHYLSTILBESTROL)Prevents miscarriages. Approved in 1940, recalled in 1971 for cervical cancer, birth defects, risk of breast cancer and infertility in children and grandchildren.

DES (DIETHYLSTILBESTROL)Prevents miscarriages. Approved in 1940, recalled in 1971 for cervical cancer, birth defects, risk of breast cancer and infertility in children and grandchildren. -

VIOXX (ROFECOXIB)Painkiller. Approved in 1999, recalled in 2004 for increased risk of heart attack and stroke after nearly 28,000 heart attacks and cardiac deaths.

VIOXX (ROFECOXIB)Painkiller. Approved in 1999, recalled in 2004 for increased risk of heart attack and stroke after nearly 28,000 heart attacks and cardiac deaths.

-

MERIDIA (SIBUTRAMINE)Appetite suppressant. Approved in 1997, recalled in 2010 for increased cardiovascular and stroke risk.

MERIDIA (SIBUTRAMINE)Appetite suppressant. Approved in 1997, recalled in 2010 for increased cardiovascular and stroke risk. -

REZULIN (TROGLITAZONE)Treats Type 2 diabetes. Approved in 1997, recalled in 2000 for liver failure and deaths. Other drugs in the same class still available include Actos (pioglitazone).

REZULIN (TROGLITAZONE)Treats Type 2 diabetes. Approved in 1997, recalled in 2000 for liver failure and deaths. Other drugs in the same class still available include Actos (pioglitazone). -

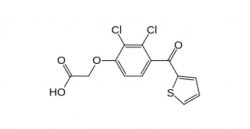

SELACRYN (TIENILIC ACID)Blood pressure drug. Approved in 1979, recalled in 1982 for hepatitis, deaths and severe liver and kidney damage.

SELACRYN (TIENILIC ACID)Blood pressure drug. Approved in 1979, recalled in 1982 for hepatitis, deaths and severe liver and kidney damage.

FDA’s Recall Notification System Needs Improvement

Not only does the FDA have issues with approving drugs with incomplete safety studies, it also takes far too long to identify dangerous drugs that make it on the market and warn the public.

A 2012 study from researchers at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston found the FDA’s recall system isn’t enough to warn health care providers or patients. The study published in the Archives of Internal Medicine found the FDA only issued notices for about half of the Class I recalls from 2004 to 2011. Class I recalls are the most serious and typically cause death or serious injury.

“The FDA offers this communication service, and we anticipate that a lot of providers may rely on it and in doing so may not be getting the information they need when drugs are recalled,” Joshua Gagne, an epidemiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and one of the authors of the study told ABC News.

While the FDA may suggest or request a recall, it has no legal authority to enforce a drug recall. Ultimately, manufacturers are responsible for pulling dangerous products off the market. This weakens the FDA’s authority to ensure safety.

The number of drug recalls surged in recent years, according to FDA data made public in 2014. Recalls nearly tripled from 499 in 2012 to 1,225 in 2013. The FDA classified 1,031 of the 2013 recalls as Class II — the “product may cause temporary or medically reversible adverse health consequences.”

In February 2017, Democratic Congresswoman Rosa DeLauro of Connecticut introduced a new bill called The Recall Unsafe Drugs Act that would allow the FDA to require drug companies to recall a product.

“As it stands, the FDA would have to go through an arduous legal process to take action against manufacturers …This is unacceptable and threatens the health and safety of American families. The Recall Unsafe Drugs Act will enable the FDA to step in and issue a mandatory recall of drugs that have been found to cause serious health consequences or death,” DeLauro told the Regulatory Affairs Professionals Society.

FDA Preemption Laws and Wyeth v. Levine

“Manufacturers remain the master of their labels even after FDA approval, and there are clear pathways through which a brand-name drug manufacturer can make changes to their label without FDA approval.”

The FDA’s drug approval process may let dangerous drugs onto the market, and drug companies may also use it to escape liability when a bad drug hurts people by claiming FDA preemption.

When drugs injure people, one of the only avenues for victims to get justice is to file a lawsuit. When Witczak killed himself allegedly because Zoloft had no warnings for suicide, Kim Witczak sued Pfizer for failing to warn them of the risk. It was a way for her to bring awareness to the issue of safety and keep other families from suffering.

FDA preemption laws threaten consumer’s rights to hold drug companies accountable for failing to warn.

How Preemption laws work to protect drug companies

-

When a drug gains FDA approval, the drug and it’s label – including the warnings and side effects – are approved as-is.

When a drug gains FDA approval, the drug and it’s label – including the warnings and side effects – are approved as-is. -

Someone develops a severe side effect that has been linked to the drug but was not included on the original warning label.

Someone develops a severe side effect that has been linked to the drug but was not included on the original warning label. -

When a person sues, the drug company claims the FDA’s approval of the drug shields them from liability.

When a person sues, the drug company claims the FDA’s approval of the drug shields them from liability.

According to FDA preemption theory, an FDA-approved, brand-name drug is exempt from liability because the agency approved the warning label as is. Preemption means that federal law — in this case the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act that authorizes the FDA to approve the release of new drugs into the market — should trump a state’s failure to warn law.

Drug manufacturers claim they cannot make a label change without FDA approval. They say the FDA’s red tape prevents them from adding label changes to warn patients and doctors. Therefore, this allows them to get away without adding warnings.

But a very important 2009 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in a historic case called Wyeth v. Levine found that FDA approval of a drug does not shield the manufacturer from liability under state law.

Wyeth v. Levine

Diana Levine sued Wyeth after she said its anti-nausea drug Phenergan caused her to develop gangrene in her hand and forearm. She had to have the infected limb amputated. In her claim, she said Wyeth failed to warn her about the gangrene risk.

Wyeth appealed, using FDA preemption, and argued that its label met the requirements of the FDA, a federal agency. So, it should not be held liable under Vermont’s state law.

The trial court and Supreme Court of Vermont ruled that the FDA requirements do not supersede state law.

The industry lobbying group Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) issued a statement in support of preemption following the ruling.

“We continue to believe that the expert scientists and medical professionals at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are in the best position to evaluate voluminous information about a medicine’s benefits and risks and to determine which safety information to include in the drug label.”

Like Wyeth, Pfizer also attempted to argue preemption in Kim Witczak’s Zoloft case.

Pfizer claimed that the state’s failure-to-warn law upon which Witczak’s lawsuit relied conflicted with the FDA’s requirements for labels. The company argued it should not be held liable for failing to warn about suicide risk. It requested that the court throw out the case. Judge James M. Rosenbaum denied Pfizer’s request in 2005.

“FDA regulations allow drug manufacturers to strengthen warning labels ‘in the interest of drug safety’ at any time without FDA pre-approval precisely so that the warnings can be ‘placed into effect at the earliest possible time’ and ‘to enable prompt adoption of such changes,’” Rosenbaum said.

A more recent example of the preemption defense occurred in Xarelto (rivaroxaban) uncontrolled bleeding litigation. Plaintiffs claim the drug’s label does not adequately warn about the bleeding risk. Right before the bellwether trials in April 2017, Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Bayer argued that FDA regulations prevented them from updating labels or creating more tailored dosing guidelines.

U.S. District Judge Eldon Fallon denied Janssen and Bayer’s motion to have some cases thrown out based on preemption.

“Manufacturers remain the master of their labels even after FDA approval, and there are clear pathways through which a brand-name drug manufacturer can make changes to their label without FDA approval,” he said in his order.

Improving the FDA’s Approval Process

“Taxpayers are paying for the agency, but we’re not treated as the customers — the companies are.”

While pointing out what could be wrong with the FDA might seem easy, fixing decades of broken practices is more complicated.

Critics and consumer advocates say one of the biggest problems is the user fees and the agency treating drug companies like its customers. The FDA should have more independent sources of independent data.

“The FDA’s current drug approval process is too dependent on the quality and integrity of research paid for the companies and too focused on approving new drugs quickly,” said Zuckerman. “Taxpayers are paying for the agency, but we’re not treated as the customers — the companies are.”

What is sorely needed are more independent voices, she said. FDA Advisory Committee meetings should include independent experts with no ties to pharmaceutical companies. These experts would help the FDA require more meaningful safety studies.

“If there is a safety concern or controversy, the FDA should welcome debates of science in an open forum,” added Kim Witczak. “For example, the antidepressant issue would have greatly benefited had this happened. Instead, those leading global experts with differing viewpoints were only given three minutes in open public forum.”

Witczak said that more independent patient’s views should make their way into the FDA’s process. Currently, most of the opinions they hear are from patient groups funded by pharmaceutical companies.

One example of this questionable process was the approval for Addyi (flibanserin), a drug for low sexual desire in women. Boehringer Ingelheim stopped working on the drug in 2010 after the FDA gave it a negative evaluation. Sprout Pharmaceuticals bought the drug and paid patients to plead to the FDA for approval. Critics said the agency approved the drug on the same questionable data after pressure from these industry-funded patients.

According to Carome, the director of Public Citizen’s Health Research Group, the FDA also approves drugs even when there are glaring safety issues. The agency then asks drug companies to conduct follow-up studies. In the meantime, the FDA exposes the public to the potentially dangerous drug.

“A better approach to protect patients from harm would be not to approve the products, but instead demand additional trials prior to approval,” Carome said.

The Aftermath of Losing a Loved One

“It was too late for our family, but if just one family is informed, then Woody’s life and death made a difference.”

Witczak’s journey after losing her husband led her to a path of activism that includes her role as a consumer representative on the FDA Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee.

“I was out of town on business when I got a call from my dad telling me that Woody, my husband of almost 10 years, was found hanging from the rafters of our garage, dead at age 37,” Witczak said, recalling that fateful day nearly 14 years ago. “Woody, my best friend, the guy I was supposed to have a family and grow old with was gone.”

Her husband’s story echoes those of others harmed by FDA-approved drugs. When Kim started fighting for patient’s rights, it was for Woody. But, she realized the issue was bigger.

“The journey for the truth has taken me to the FDA, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Congress, the courts and media,” Witczak continued. “I work with a huge network of patient safety activists across the country that work on a variety of issues. Many of them came into this work as a result of a harm or adverse experience.”

Witczak stresses education. She says consumers should challenge their physicians and find out all they can about a drug. The FDA also needs more authority to compel recalls and police drug and device companies.

“It was too late for our family,” she said. “But if just one family is informed, then Woody’s life and death made a difference.”

Calling this number connects you with a Drugwatch representative. We will direct you to one of our trusted legal partners for a free case review.

Drugwatch's trusted legal partners support the organization's mission to keep people safe from dangerous drugs and medical devices. For more information, visit our partners page.