Brand-name prescription drug prices in the U.S. have increased nearly 100 percent in the past six years. A major reason for the climbing costs is a lack of generic competition. Without competition from lower-cost, generic drugs, branded drug companies set their own prices and increase those prices as often and as much as they wish. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration cannot control the cost of drugs, but it has the power to approve generic versions of drugs, giving Americans cheaper options. Unfortunately, drug companies are abusing government processes to block generic competition and keep drug prices rising.

Editors carefully fact-check all Drugwatch content for accuracy and quality.

Drugwatch has a stringent fact-checking process. It starts with our strict sourcing guidelines.

We only gather information from credible sources. This includes peer-reviewed medical journals, reputable media outlets, government reports, court records and interviews with qualified experts.

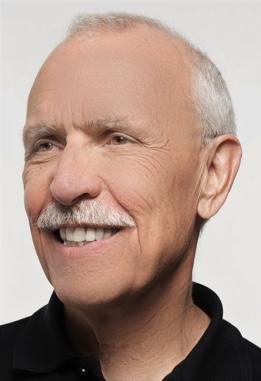

As David Mitchell stared at his full-body X-ray, he knew he could never look at such images again.

“It was too ugly,” Mitchell recalled. “I have holes in my bones — in my skull, in my pelvis, in my arms.”

Doctors diagnosed Mitchell with an incurable blood cancer called multiple myeloma in November 2010. Although there is no cure for multiple myeloma, the disease is treatable with very expensive drugs.

“Right now, I’m on a two-drug combination,” Mitchell said. “I get it in a five-hour infusion dose, and every time they give it to me, the retail price is $20,000. I will have this two-drug combination 22 times over the course of a year, which means that $440,000 worth of drugs — literally — is keeping me alive.”

But, drugs don’t work if people can’t afford them, said Mitchell, whose medication is currently covered by insurance.

“This experience of having multiple myeloma has brought me face-to-face with the challenges people confront trying to deal with high drug prices,” he said.

Mitchell and his wife, who is also a cancer survivor, launched Patients for Affordable Drugs on February 22, 2017. The national patient organization focuses on amplifying the voices of patients and mobilizing patients to support policy changes that will lower drug prices. In just six months, Mitchell and his team collected about 8,000 patient stories.

“These are stories that come from every region of the country — people with all sorts of different diseases. We hear this over and over again — people who are choosing between food and drugs, people who are choosing between paying rent and drugs.”

Across the nation, people who require daily medication are cutting their pills in half or skipping doses because they can’t afford to take the full dose, Mitchell said. People with Type 1 diabetes are trying to manage their disease with diet and exercise and waiting until their blood sugar spikes dangerously before giving themselves insulin. People with rheumatoid arthritis are in terrible pain and can’t take the full dose necessary to manage their pain because the drugs are too expensive.

“We had one woman who wrote a story and said, ‘I really have to consider whether I should just give up the fight and stop taking the drugs because if I keep taking the drugs, I’ll bankrupt my family,’” Mitchell said. “The stories are excruciating, and people are angry and upset, and they don’t understand how this could be happening to them in the United States of America.

Prescription drug prices in the U.S. have been rising for several years. Some drugs in 2022 increased by more than $20,000 or 500%.

Between July 2021 and July 2022, there were 1,216 products whose price increases exceeded the inflation rate of 8.5% for that period. The average price increase for these drugs was 31.6%.

U.S. Drug Prices by the Numbers

More and more Americans are finding the cost of drugs to be unreasonable while less and less are saying prescription drugs have improved their lives, according to a 2016 Kaiser Health Tracking Poll. The poll also found:

- In 2015, 62 percent of Americans

- said prescription drugs have made their lives better — down from 73 percent in 2008.

- An estimated 77 percent of Americans

- in 2016 said drug prices were too high compared to 72 percent in 2015.

- And a large majority (78 percent) of Americans

- say there should be a limit on the amount drug companies can charge for high-cost drugs for illnesses like hepatitis or cancer. (As of May 2017, a 30-day supply of Gilead Sciences hepatitis C drug Harvoni cost $87,800, an increase of $13,800 from 2016.)

Overall, brand-name drug prices in the U.S. have increased 98.2 percent since 2011, with the average price of prescriptions climbing 16.2 percent in 2015 alone, according to Express Scripts.

And patients with commercial health insurance are paying 25 percent more in out of-pocket expenses for branded prescriptions than they did in 2010, according to IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics.

What’s worse: prescription drug prices are increasing dramatically even though the drugs’ ingredients often times stay the same. Although the FDA is charged with ensuring drugs are safe and effective, the federal agency has no legal authority to regulate drug prices.

“Physicians strive to provide the best possible care to their patients but increases in drug prices – without explanation — can affect their ability to offer patients the best possible drug treatments.”

Competition Is Key

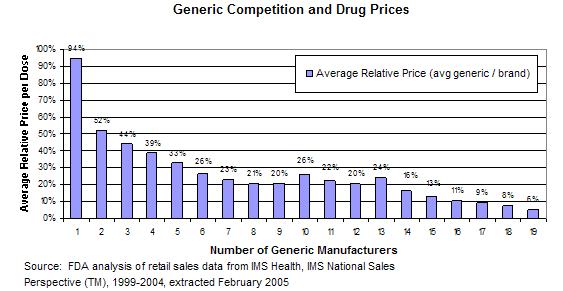

A number of factors affect drug pricing in the U.S. A major contributor is generic competition.

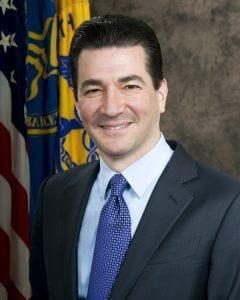

“Over the last decade alone, competition from safe and effective generic drugs has saved the healthcare system about $1.67 trillion,” FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb said in a June 2017 statement. “When generics are dispensed at the pharmacy, the immediate savings to each of us are clear.”

In the U.S., when a new drug (brand-name drug) comes to market a company gets exclusivity for a period of time so that it can make money and be repaid for the investment it made in research and innovation. But, at the end of that exclusivity period, branded drug companies are supposed to allow generics — or copycat drugs that are deemed as safe and as effective — to come to market so that competition drives the price down.

“Data indicate that consumers see significant price reduction when there are multiple FDA-approved generics available,” FDA spokeswoman Sandy Walsh said in an email to Drugwatch.

In fact, generic prices can be as much as 90 percent less than brand-name prices, according to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).

“The first generic competitor’s product is typically offered at a 20 percent to 30 percent discount to the branded product,” FTC spokeswoman Betsy Lordan said in an email to Drugwatch. “Subsequent generic entry creates greater price competition, with discounts of 85 percent or more off the price of the branded drug.”

Drug Companies ‘Game’ the System

The generic drug approval process is governed by the Hatch-Waxman Act. Congress enacted the act in 1984 to make sure consumers would have access to lower-cost generic drugs while still preserving incentives (patent protection and market exclusivity) for companies to make new drugs.

Since the act’s inception, however, some branded companies have used different strategies — including conduct that violates the antitrust laws — to delay generic competition and effectively extend their marketing exclusivity.

As of May 2017, the FDA identified some 150 drugs that could have generic competition but do not, which means patients are paying more for the drugs.

“We know that sometimes our regulatory rules might be ‘gamed’ in ways that may delay generic drug approvals beyond the time frame the law intended, in order to reduce competition,” Walsh said. “We know that high drug prices have a direct impact on patients — too many Americans are priced out of the medicines they need.”

“Although widespread introduction of generic drugs has saved Americans hundreds of billions of dollars in drug costs, some companies have exploited the ability to delay generic entry through abuse of government processes.”

Pay-for-Delay

One way branded drug companies delay generic competition that lowers prices is through “pay-for-delay” agreements. Pay-for-delay agreements — also known as “exclusion payment” or “reverse payment” agreements — are settlements in patent litigation between brand-name and generic pharmaceutical companies.

As part of a settlement, the branded drug company will agree to pay a generic competitor to drop a patent challenge and hold its competing, lower-cost product off the market for a certain period of time.

Pay-for-delay agreements are great for the drug companies because brand-name prices stay high and the branded and generic companies share the benefits of the brand’s monopoly profits, according to the FTC. Consumers, on the other hand, lose out on generic prices.

These agreements are estimated to cost American consumers $3.5 billion per year and delay generic entry for an additional 17 months, according to the most recent estimates from the FTC.

A 2010 FTC staff study found pay-for-delay agreements protected at least $20 billion in sales of brand-name pharmaceuticals from generic competition.

“Pay-for-delay agreements continue to deprive consumers of the ability to choose lower-cost medications and impose considerable costs on consumers,” Lordan said.

For example, a consumer paying $400 per month for a branded drug (as opposed to a generic price as low as $40 per month) is forced to pay as much as $360 more per month for prescription drugs. With the extra 17-month delay, the consumer ends up paying $6,120 in additional expenses.

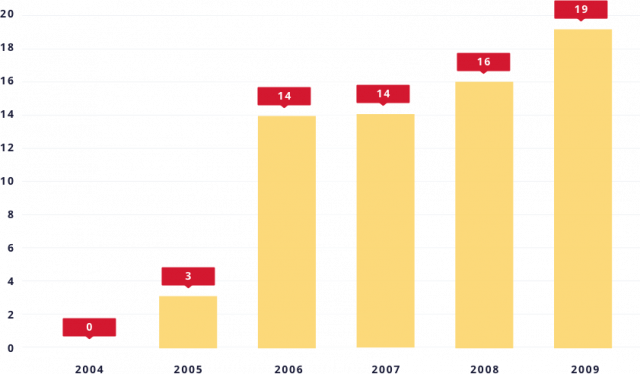

From zero to 66 in five years

In 2013, the Supreme Court explained in FTC v. Actavis that pay-for-delay agreements can violate the antitrust laws. Still, Congress has yet to definitively declare the practice illegal.

“This is one area that Congress can act to ensure that we have the competition that Congress intended,” Mitchell said. “It needs to be clarified and absolutely explicitly illegal.”

In the six years prior to 2005, FTC enforcement actions against pay-for-delay deterred their use, and an appellate court in 2003 held that pay-for-delay agreements were automatically illegal.

However, since 2005, some appellate courts have misapplied the antitrust laws to uphold these agreements, and pay-for-delay agreements have reemerged.

“Pay-for-delay deals are a bad prescription for America; when drug companies agree not to compete, consumers lose,” former FTC chairman Jon Leibowitz said in a January 2010 statement. “Ending this practice as part of healthcare reform is one simple, effective, and straightforward way for Congress to help control costs.”