GAO Investigates Morcellator Link to Uterine Cancer

Congressional watchdogs were called in to evaluate the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s approval and reporting process involving power morcellators. The Government Accountability Office (GOA) found the FDA failed to adequately protect the public.

After media reports emerged about medical devices called power morcellators and their suspected link to uterine cancer, Congressional leaders called in their watchdogs to investigate.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) confirmed what many patients, lawyers and medical experts already knew. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) lacks complete efficiency and, in the case of power morcellators, failed to adequately protect the public.

The devices are used in surgical treatments to morcellate, or chop up and eradicate, benign fibroid tumors. But power morcellators can also disperse previously hidden cancer cells, promoting growth.

Two Pennsylvania politicians, Congressman Mike Fitzpatrick and U.S. Senator Bob Casey Jr., called for an investigation after learning about Dr. Amy Reed’s fatal experience with cancer and power morcellators.

Other women stepped forward after hearing about the Boston-area woman’s death from a smooth-muscle cancer called leiomyosarcoma.

Reed’s husband, Hooman Noorchashm, said the GAO report brought no surprises for him.

“We knew what the answer was going to be,” Noorchashm told Drugwatch. The report said power morcellators are causing harm at a certain rate because there are no federal mandates in place to require self-reporting of adverse events by those in the best position to do so — the doctors and hospitals.

GAO Study Finds FDA Failure

Philly Magazine reported succinctly that GAO’s report concluded that “the FDA system failed.” Moreover, JAMA stated that according to the report, “the FDA was aware that laparoscopic power morcellators could spread cancerous tissue when the agency approved the first such device in 1991.”

GAO reported that prior to receiving a single adverse event report, the FDA understood the risk of a woman possibly having an unsuspected cancer that could be spread using a power morcellator. But the FDA thought this risk was low “based on available information.”

At the time, the FDA believed the chances that a woman undergoing fibroid (uterine tumor) removal would also have an unsuspected, difficult-to-diagnose uterine sarcoma ranged from about 1 in 1,000 to 1 in 10,000 women.

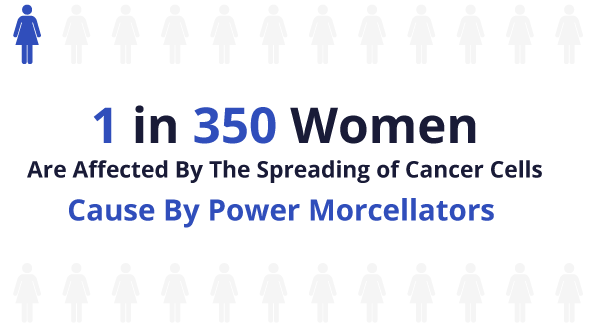

Those numbers have since shifted to estimates closer to 1 in 350 women for one type of cancer after an evaluation of reports beginning in December 2013.

Case Studies Concluded Cancer Risk

FDA officials acknowledged to investigators that news articles about the risk of spreading tissue (noncancerous and cancerous) with power morcellators were published before the agency received the first adverse event reports.

But these officials also noted that, at that time, “there was no consensus within the clinical community regarding the risk of this occurring, particularly for cancerous tissue.”

GAO identified 30 such articles published between 1980 and 2012 that mentioned or concluded a risk with the use of a power morcellator, or that advised the need of a physician to remove all tissue fragments following a surgical procedure involving the morcellation of uterine fibroids.

However, GAO also found that most of the articles involved cases studies and were limited in scope, with one case study published in 2010 looking at just a single patient.

While no one article identified by the GAO provided an exact risk estimate, one study published in 2012 examined 1,091 instances of uterine morcellation, discovering that the rate of unsuspected cancer (uterine sarcoma) was actually nine times higher than the rate quoted to patients at the time (1 in 10,000).

The study concluded that “uterine morcellation carries a risk of spreading unsuspected cancer.” Still, the FDA did not take any action until it received the first adverse event reports in December 2013.

FDA Approval Process

In its report, the GAO found that the FDA cleared 25 submissions for laparoscopic power morcellators for the U.S. market between 1991 and 2014. The FDA cleared these devices through its premarket notification process governed by Section 510(k) of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act. Under this rule, the FDA reviews information submitted by a device manufacturer and determines whether the device is substantially equivalent to another already legally marketed device, called predicate devices.

Essentially, any device determined to be substantially equivalent is cleared to be marketed, as long as it does not raise different questions of safety and effectiveness. GAO found that the FDA determined all 25 of the 510(k) submissions for power morcellators to have the same intended use as their predicates, and while six had new technological characteristics, these differences did not alter the intended effect of the device.

In clearing the first of the 25 power morcellators, the FDA relied upon a predicate device known as an arthroscopic surgical system, an electromechanical system for cutting tissue during minimally invasive surgeries performed on joints, GAO found.

In approving the other 24 power morcellators, the most recent being cleared in May 2014, the FDA determined that each one was equivalent to at least one power morcellator previously cleared before it.

As reported by Boston Magazine in 2016, “there hadn’t been any pre-market testing of the morcellator in women with fibroids; the FDA didn’t require it.” Instead, through the FDA expedited approval process, power morcellators were “grandfathered into use.”

FDA Adverse Event Reporting Process

When a new medical device hits the market, manufacturers and importers must comply with certain medical-device reporting requirements. According to the GAO report, under these requirements, “these parties must report device-related adverse events, including events that reasonably suggest a device has or may have caused or contributed to a death or serious injury,” within an appropriate timeframe.

Consumers and other parties may voluntarily report adverse events directly to the FDA. The agency maintains databases that record both mandatory and voluntary reports of device-related adverse events.

While these adverse event reports are often the first signal to the manufacturer and the FDA that a problem exists, the FDA told GAO that information from these reports “can be limited.”

Some identified areas of limitations include:

- Incomplete or erroneous reporting – where key data are not reported or where the information is inaccurate.

- Untimely reports – where the report does not always reflect “real time” reporting, as some events occurred years prior.

- Underreporting – where some adverse events are not reported at all.

Just after the release of the GAO report in February 2017, The New York Times reported that doctors and hospital officials told investigators with the accountability office that “before November 2014, when the FDA explicitly stated that cancer spread after morcellation was an adverse event that had to be reported, they would not have regarded it that way or reported it.”

Prior to that notification, these health care professionals acknowledged that they were under the assumption that an adverse event from a device only related to a failure of the device itself.

The report said physicians and hospitals concluded, in the case of the power morcellators, that the devices were doing “exactly what they were supposed to do – slicing up tissue.”

“The passive reporting of adverse events is a weak system.”

The government report noted that its procedure is “passive, relying on ‘adverse event’ reports to the FDA from doctors, hospitals, drug and equipment manufacturers, and consumers.”

And, in the circumstance surrounding power morcellators, the first adverse event report was not received until 2013, from Reed, the Boston-area doctor.

Once that case was “widely covered by the news media,” according to The New York Times, more reports began coming in, amounting to a total of 285 reports by September 2016.

Probe Took Year to Obtain Sufficient Evidence

According to the GAO, with “virtually the entire federal government subject to its review,” the agency issues a steady stream of reports and testimony before Congress, usually contributing over 900 separate products each year. The agency operates under “strict professional standards of review,” with all numbers and statements of fact presented in its work subject to thorough checks and references.

The agency stated in this report that the audit was conducted from February 2016 to February 2017 “in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.” The government office went on to explain that those standards require “that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.”

The agency also contacted officials from 10 professional societies and other organizations that have a potential interest in the use of power morcellators, and three health care providers that performed certain gynecological procedures that could involve the use of the devices. The agency also contacted all 12 manufacturers making and distributing power morcellators previously cleared by the FDA for the U.S. market.

While this took a year, many of the women injured by the controversial device were not afforded the same period in which to save their lives. Many of the women diagnosed with aggressive uterine cancers after undergoing procedures involving a power morcellator died within one year of receiving the news.

This reality actually necessitated an order to speed up the discovery process and scheduling of depositions (oral testimony) in a multidistrict litigation (MDL) suit against the manufacturers of the devices.

Widower Calls for ‘Cataclysmic Shift’

In its 2017 report, the GAO pointed out that many questions still remain regarding the use of power morcellators in the treatment of uterine fibroids, including varying stakeholder opinions regarding the risks related to the use of the device. One concern noted by FDA officials was that there is limited information available to assess how the risk of spreading cancerous tissue is affected when morcellation is performed using manual morcellation techniques, such as a scalpel versus power morcellation.

The report noted that officials from one professional society offered the same question, stating that they were “not aware of any reliable data showing that power morcellation spreads tissue any worse than other morcellation techniques.” In a way, Noorchashm actually concurs with that statement, pointing out to Drugwatch that there needs to be a “cataclysmic shift in the way gynecologists think about this,” in that “the real problem is actually the act of morcellation [itself].”

Professional societies are also questioning the FDA’s methodology in concluding its estimate of cancer risk in women undergoing surgical treatment of uterine fibroids. These societies pointed out limitations with the FDA’s assessment, including concerns regarding “keywords” used by FDA officials to find the studies included in its estimate.

One professional society stated in an open letter to the FDA that a more appropriate estimated risk would be in the range of about 1 in 1,500 to 1 in 2,000; although, FDA officials noted that their conclusions are confirmed by “more recently representative published studies,” that are generally consistent with the agency’s estimate.

However, two professional societies contacted by the GAO still assert continuing questions as to the long-term effects to patients of the FDA’s guidance deterring the use of power morcellation in laparoscopic surgeries. The societies argued that this may lead to an increased use of abdominal hysterectomies, which is associated with other risks to women including larger incisions, slower recovery time, and higher mortality rates and complications compared to laparoscopic hysterectomies.

But the FDA responded that a 2016 study, which reported a decline in the use of power morcellators in hysterectomies since the FDA issued its guidance in November 2014, found “no increase in complications from abdominal hysterectomies.” According to a 2022 research study, laparoscopic power morcellator use decreased by 9.5% for each quarter elapsed after the FDA warning period.

FDA Pledges to ‘Generate Better Information’

The FDA acknowledged in a statement that it agreed with the GAO’s findings and that it has “noted the shortcomings of the current passive post-market surveillance system and has been taking steps to establish a better system to evaluate device performance in clinical practice.”

The agency reported its plan to “generate better information in the future,” including plans to work with hospitals to identify a system that quickly identifies life-threatening problems caused by medical devices. Other noted improvements included an ongoing review of new technologies, such as morcellation systems, and a national registry to collect data on the treatment of fibroids, as well as the establishment of a National Evaluation System for health technology “to more efficiently generate better evidence for medical device evaluation and regulatory decision-making.”

While Crosse pointed out a way in which the FDA could “take a more active role” by reviewing hospital records in order to discover adverse events that are going unreported and search for additional “warning signs,” she also acknowledged that there’s a cost involved in putting such data systems in place, and that it’s not cheap.

Hooman Noorchashm, husband of Dr. Amy Reed who died as a result of leiomyosarcoma is staying positive. As he stated to Philly Magazine, “This is a real opportunity for the Trump administration to acknowledge and address a deadly women’s health issue by creating a robust adverse-outcomes reporting requirement for individual expert practitioners through an executive action.”

Noorchashm, using the GAO report as one of his sources, is calling for radical changes including the elimination of the current 510(k) regulation used in the approval of medical devices. Noorchashm says that as the FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health operates now, it is “entirely unsafe.”

Calling this number connects you with a Drugwatch representative. We will direct you to one of our trusted legal partners for a free case review.

Drugwatch's trusted legal partners support the organization's mission to keep people safe from dangerous drugs and medical devices. For more information, visit our partners page.