Disease Mongering and Drug Marketing

Editors carefully fact-check all Drugwatch content for accuracy and quality.

Drugwatch has a stringent fact-checking process. It starts with our strict sourcing guidelines.

We only gather information from credible sources. This includes peer-reviewed medical journals, reputable media outlets, government reports, court records and interviews with qualified experts.

The absolute, essential element for any business that wishes to succeed consists in discovering what the buying public needs and then fulfilling that need.

Sometimes a product or service exists for which a need cannot be determined easily. When that situation occurs, businesses must turn to advertisers, for conventional wisdom dictates that without the need, their product or service will languish on the shelf.

In actuality, the things that people truly do need – food, clothing, shelter, etc. – will always be found, if available, without advertising.

So really, advertising exists to purvey what people don’t truly need. The real job of the advertiser, then, is to create a need where none exists. Once the need is created, a product or service can generally be proffered to fill it.

Drug Companies Profit by Expanding the Market for a Drug

Pharmaceutical companies manufacture drugs. And research and development of modern pharmaceuticals is an expensive and time consuming affair.

Drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are vetted during years of costly experimentation and clinical trials, and often they are sanctioned for a limited or very specific use.

When the cost of creation and manufacture of a given drug is greater than its return on investment, pharmaceutical companies must figure out ways to boost the product’s appeal and usage so that they can make a profit. And so they, too, will turn to advertisers to create a need where none has previously existed.

When the product is a cure, it stands to reason that the created need must be a disease.

Defining Disease Mongering

The effort to sell pharmaceuticals based on the creation of perceived need is known as “disease mongering,” a term introduced by health-science writer, Lynn Payer in her 1992 book “Disease-Mongers: How Doctors, Drug Companies, and Insurers Are Making You Feel Sick.”

Payer defined disease mongering as “trying to convince essentially well people that they are sick, or slightly sick people that they are very ill.” Pharmaceutical companies spend a great deal of money – twice the amount they spend on research and development – on manipulative and insidious advertising that preys upon the fears and insecurities of consumers.

By creating diseases where none heretofore existed, or inflating common maladies into alarming health issues for which their drug is the only acceptable treatment, these companies make enormous profits on products that were not initially designed for the reasons which they are now being dispensed.

The benefits of disease mongering are certainly lucrative to pharmaceutical companies. A study on the same topic by researchers at Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology revealed that an increase of as little as 10% in direct-to-consumer advertising of drugs within a specific drug class correlated to a 1% increase in sales in that class.

Big PhRMA Spends More Money on Marketing than on Research

That means that for every dollar drug companies spend on DTCA, in that same year they make $4.20 in pharmaceutical sales. In the year 2000 alone, the practice of DTCA generated an additional 12% increase in the sale of prescription drugs. While that amount doesn’t seem like a substantial amount, it correlated to an additional $2.6 billion in profits for Big Pharma. Not a bad return on investment.

Take the recent boom in the anti-depressant market. Anti-depressants rank second in overall prescriptions in the U.S. According to a study published in the Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, as the makers of these drugs spent more money on direct-to-consumer advertising, the number of prescriptions increases.

Pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly marketed the anti-depressant Sarafem to women in order to combat the mood swings, irritability, and other symptoms brought on by their menstrual cycles each month. The ads featured happy, beautiful women that claimed these symptoms were caused by a new disease: Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD).

What the drug manufacturer didn’t mention was that Sarafem was simply a new name for Prozac, and Eli Lilly needed a new brand to sell after their exclusive patent on that famous drug ran out.

Eli Lilly has a long history with direct-to-consumer advertising. It was one of the drug companies that pioneered the art of deceptive marketing. In 1982 the U.S. Food & Drug Administration ordered the company to retract print materials featuring their drug, Oraflex, because they were misleading and did not warn about possible side effects.

Apparently, old habits die hard. In recent news, Eli Lilly has been involved in lawsuits for not disclosing that the diabetes drug Actos may cause bladder cancer.

These lawsuits shed light on another problem related to disease mongering. These so called miracle pills often lead the way to more sickness.

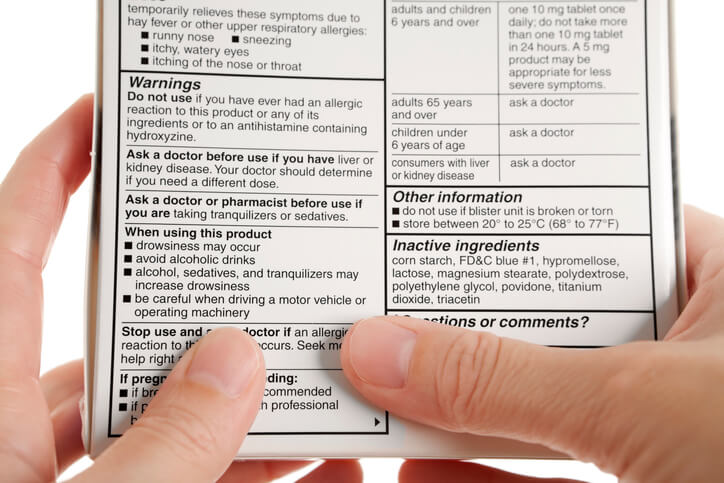

Consumers are constantly bombarded with disease mongering ads that convince them that they have a new disease and offer a cure, but little is said about the possible safety risks. The lax FDA regulations allow drug companies to advertise their products without revealing all the possible side effects.

Modern disease mongering may have gotten its start in the late 19th century with the invention and peddling of Listerine, originally used as a surgical antiseptic because of its high alcohol content. Listerine’s inventors, Dr. Joseph Lawrence and Jordan W. Lambert also marketed their product in a concentrated form as a floor cleaner and a treatment for gonorrhea.

Disease Mongering has Been Around for a Long Time

In 1895, they began to sell it to dentists as an oral care product and in 1914, it became the first over-the-counter mouthwash sold in the United States. By the 1920’s, the Lambert Pharmacal Co. knew it had a cure – now it needed a disease. So they concocted “halitosis,” formerly an obscure medical term for malodorous breath.

Advertisers promoted Listerine as the cure for halitosis, which they said could ruin one’s social life and be a detriment to a happy marriage or fulfilling career. Soon people all over America were “suffering” from halitosis.

Listerine’s progenitors latched onto the simple yet brilliant tactic still being used by the pharmaceutical industry today – seizing upon an ordinary, everyday occurrence and raising it to the level of pathology, which if not attended to will cause irreparable harm to one’s future health or happiness.

Corollaries to this dynamic include taking a common symptom that could mean anything and making it sound as if it is a sign of a serious ailment – or giving a relatively benign condition a “scientific” name.

It’s important to note that the disease monger is not saying certain conditions don’t exist – they do. But their job is to exaggerate wildly the incidence and relevance to scare people into imagining the worst. That makes them rush out to buy a drug guaranteed to alleviate or minimize the danger of a disturbing situation.

Modern Illnesses that have Made Billions for Drug Companies

Some modern “illnesses” that critics contend have been mongered by the major drug companies include: erectile dysfunction, female sexual dysfunction, bipolar disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), irritable bowel syndrome, “male pattern” baldness, acid reflux disease, and restless leg syndrome.

Predictably, the pharmaceutical companies assert that their products all have necessary medical applications, and do not agree with the critique of disease mongering. According to Alan Goldhammer, Associate Vice President for Regulatory Affairs for the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), the industry’s main trade group, “Our [industry’s] job is to look for cures, not to create disease.”

However, the case can be made that each of the above conditions have been capitalized upon by the various pharmaceutical companies for the sole purpose of creating a lucrative market out of frightened and ill-informed consumers, eager to find a cure for the latest, albeit specious, ailment they’ve seen on TV. The following is only one example of a successfully mongered disease.

Restless Leg Syndrome (RLS) is a real but relatively rare neurological disorder characterized by an irresistible urge to move one’s body to stop uncomfortable or odd sensations. It generally occurs in the legs. Its medical name is Willis-Ekbom disease and its most commonly associated medical condition is iron deficiency. Very few people have RLS, and more than 60 percent of those cases are familial, meaning that the disorder is genetically inherited. But many other people are prone to believe that the restlessness in their legs must have a cause other than too much stress, not enough sleep, or too much caffeine or alcohol.

For these people, GlaxoSmithKline, the world’s second largest drug company, has Requip (Ropinirole hydrochloride), a drug originally granted FDA approval for the control of symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, but given approval for RLS in May 2005, despite its long list of potentially detrimental side effects, including dizziness, nausea, somnolence (falling asleep), viral infection and hallucinations.

Notwithstanding, by the first quarter of 2006, the number of weekly new prescriptions for Requip in the U.S. was four times that at the time of product launch, thanks to heavy doses of advertising and free physician samples. In 2005, the sales of Requip were approximately $250 million. In 2006, Requip sales were closing in on half a billion dollars. By 2015, the U.S. market for Requip is estimated to be $1.7 billion. Does RLS exist? Yes. Do millions of people suffer from it? Probably not. Is GlaxoSmithKline making a lot of money on Requip? You betcha!

Big PhRMA Influence Soothes Government Concern

Concern over disease mongering has also reached the White House, largely in part to its negative impact on the cost of healthcare. In 2009, Democratic Representative Bart Stupak of Michigan, chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, fought to approve a two-year advertising ban on new drugs.

However, Big Pharma and its lobbyists have been largely successful in being able to maintain business as usual. The pharmaceutical lobbying group Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) quickly released its own Guiding Principles on Direct to Consumer Advertisements about Prescription Medicines in a bid to avoid government regulation.

The U.S. Food & Drug Administration has pledged to tackle this issue and begin a study on the effects of disease mongering, but the results of this study aren’t likely to be released any time soon.