Eli Lilly & Co.

Eli Lilly and Company is one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies responsible for mass producing some of the most revolutionary medicines of the 20th century. It has also faced lawsuits over its psychiatric medicines and government scrutiny over insulin price hikes in recent years.

Eli Lilly is among the largest pharmaceutical company in the world based on 2021 revenue of more than $28.31 billion. The company’s highest selling drugs for the year were Humalog (insulin) with $2.7 billion in sales, erectile dysfunction drug Cialis with $2.4 billion, and lung cancer drug Alimta with $2.2 billion in sales.

Five of the company’s best selling drugs, responsible for 21% of the company’s revenues, face patent expirations by 2023. These include Cialis, scheduled to go off-patent in November 2017. Once these patents expire, the company expects lost revenue from competition with generic versions.

Founded by a Civil War veteran, the company would be at the forefront of 20th century medical innovations – becoming the first company to mass-produce insulin, penicillin and the Salk Polio vaccine and changing the way Americans perceived mental health care with the introduction of Prozac.

It is the largest manufacturer of psychiatric medicines and one of the three largest insulin manufacturers in the world.

As of 2017, more than one in five of Lilly’s employees, and nearly a quarter of its revenues, were devoted to research and development of new treatments. Lilly products were manufactured by plants in 13 countries and sold in 120 nations around the world.

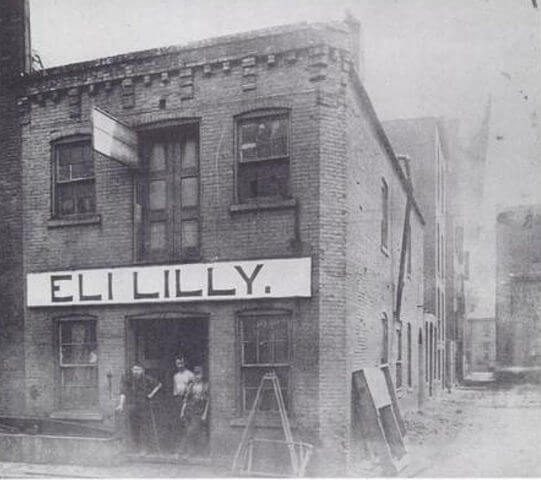

The Civil War and Science Shape Eli Lilly and Company’s Early History

Eli Lilly was only 16-years-old and a recent graduate of the class of 1854 at what is now DePauw University when he began a pharmacist apprenticeship in Lafayette, Indiana. In 1861, the Civil War would interrupt his career, until then spent working in various drugstores around the region. Joining the Union Army, Lilly rose to the rank of colonel before he turned 27, leading artillery forces until he was taken prisoner by the Confederacy.

Witnessing fellow officers die in an Alabama prisoner of war camp gave Lilly a firsthand view of the ravages of 19th-century disease that he undoubtedly carried with him for the rest of his life.

At a time when unreliable and often dangerous “cure-all” products were sold to an unsuspecting public, Lilly wanted to produce reliable, high-quality medicines. He set out to create a line of medical products specifically for physicians to use in treating their patients. He opened Eli Lilly and Company in an 18-by-40-foot, two-story building in Indianapolis on May 10, 1876.

In 1886, he hired full-time scientists chemist Ernest Eberhardt and botanist Walter Evans to research new products. His company would continue to devote a sizable portion of its operation to scientific research, spending more than $5 billion a year on research and development by 2016.

Insulin, Innovation Spur Lilly’s 20th Century Growth

Even though Lilly died in 1898, his Civil War experiences and focus on science in developing new drugs would continue to shape his company’s culture through the 20th century. Eli Lilly and Company would also become an innovator in new and breakthrough drug technology, allowing it to become one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical manufacturers.

In 1923, when diabetes was nearly always fatal and had no adequate treatment, Lilly worked with the University of Toronto to develop the first commercially produced insulin, which the company branded as Iletin. Derived from animal insulin, J.J.R. McLeod and Frederick Banting, the Scottish and Canadian researchers who developed Iletin, received the 1923 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work.

Two Lilly scientists, George Minot and William Murphy, working alongside William Whipple of the University of Rochester, would win a Nobel Prize in 1934 for their development of drugs during the 1920s to treat pernicious anemia, a blood and kidney disorder.

As the country weathered the Great Depression, Lilly kept its workers on the job and increased sales to $13 million in 1932. In 1934, it opened its first international subsidiary in the UK.

During the First World War, Lilly had partnered with the American Red Cross to create the Lilly Field hospital, treating troops of all nationalities for two years in France. During the Second World War, the company produced medicines carried by American troops in flight and field kits. In early 1944, the company became the first to mass produce penicillin, leading Lilly into the field of infectious disease prevention even as the antibiotic was rushed to allied battlefields in Europe and across the Pacific.

By 1950, the company had grown to more than 5,500 employees with sales reaching $159 million.

In 1955, Lilly became the first pharmaceutical company to manufacture and distribute the Salk Polio Vaccine. The company expanded into cancer treatment in 1961, developing and marketing Velban (vinblastine), a chemotherapy drug used to treat several types of cancer. By the mid-1970s, Lilly topped $1 billion in sales for the first time, with 23,000 employees spread across 39 international subsidiaries or divisions.

In 1982, the company released the diabetes drug Humulin. Lilly used recombinant DNA technology for the first time to produce a medicine for humans. Humulin is an insulin identical to that produced in the human body.

Lilly Redefines and Dominates Psychiatric Drug Market

Approved in 1987, Prozac (fluoxetine HCl) may be Lilly’s most famous drug. It was also one of the company’s most successful. The medicine to treat clinical depression accounted for $2 billion in sales in 1994 – almost a third of the company’s total revenue that year.

The antidepressant was the first in a class of drugs called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI). SSRIs target a single chemical in the brain, serotonin. Prior to Prozac, antidepressants targeted several brain chemicals.

Prozac was not only a new way to treat major depression; the drug also became a pop culture touchstone and helped Americans perceive mental health care in a more positive light.

Lilly followed Prozac with Zyprexa (olanzapine) to treat schizophrenia in 1996 and Cymbalta (duloxetine hydrochloride) to treat major depressive disorder in 2004.

Eli Lilly and Co. Investigated, Named in Lawsuits for Insulin Price Hikes

In 2016, Humalog insulin was Lilly’s biggest selling product and the company was one of the world’s three largest insulin producers. In 2017, the company announced that it had responded to two investigations into possible insulin price-fixing.

In an April 2017 filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the company reported it had received “civil investigative demands” – requests for documents and other evidence – from the attorneys general of Washington state and New Mexico who were investigating insulin price hikes. The company said the Washington investigation sought information “relating to the pricing of our insulin products and our relationships with pharmacy benefit managers.”

Lilly said it was cooperating with both investigations.

The probes follow 15 years of rapidly rising insulin prices and increased public, political and regulatory scrutiny on the cost of the medicine vital to keep people with type 1 diabetes alive.

A 2016 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that insulin prices in the U.S. nearly tripled between 2002 and 2013. By January 2017, a month’s supply of insulin could cost as much as $900. The American Diabetes Association reported that some patients were resorting to a risky practice of “rationing” doses to make ends meet. Taking too small a dose, skipping doses or using expired insulin to save money can result in severe kidney damage or death for people with type 1 diabetes.

News investigations have documented Lilly and the other two largest insulin manufacturers – Novo Nordisk and Sanofi – have raised insulin prices in near lockstep for years. Bloomberg, which first reported on the pattern, called it “shadow pricing,” meaning one company shadowing another’s price increase by almost the same amount. The difference is usually so small there is no competitive advantage for one product over the others.

In November 2016, two members of Congress, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Rep. Elijah Cummings, authored a letter to the U.S. Justice Department and Federal Trade Commission calling for investigations into the price hikes by the three companies and others.

In March 2017, Lilly and the two other companies were named among the defendants in a 69-count class action lawsuit in a New Jersey federal court. The suit claims the manufacturers colluded with pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) to fix insulin prices and violated federal antitrust laws. The three PBMs named in the suit – CVS Health, Express Scripts and OptumRx – control 80 percent of the PBM industry, overseeing prescription coverage for 180 million Americans.

Lilly reported in April 2017 that it was also named in at least two more similar class action lawsuits over insulin pricing. The company denied the allegations in all three lawsuits and promised to defend against them “vigorously.”

Just two months later, in May 2017, Lilly raised the price of Humalog by 7.8 percent to $274.70 for a 10 ml vial. Novo Nordisk followed suit raising the price of its competing insulin 7.9 percent to $275.58 – a difference between the two products’ prices of just 88-cents.

In its April 2017 SEC filing, Lilly said revenue for Humalog had increased 24 percent to $449.1 million in the U.S. in the first three months of 2017. Worldwide, Humalog sales rose 17 percent to $708 million.

In May 2023, the class-action lawsuit against Lilly ended in the company agreeing to pay the plaintiffs $13.5 million. According to court documents filed on May 26 in New Jersey, Lilly also agreed to a cap on out-of-pocket costs for its insulin at $35 per month for four years.

Problematic Medications Prove Costly for Eli Lilly and Company

Lilly has also faced financial setbacks and regulatory scrutiny over several high-profile medications in recent years. Lawsuits, settlements and even a record criminal fine have affected the company’s finances.

In 2000, the FDA approved Lilly’s Zyprexa (olanzapine) for treatment of psychotic disorders including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Zyprexa works by binding receptors in the brain, reducing delusions and hallucinations.

Studies later linked the drug to weight gain and increased blood sugar levels, and by 2007, Lilly had paid $1.2 billion to settle more than 26,000 lawsuits filed by people who claimed in court documents they developed diabetes or related conditions after taking Zyprexa.

The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) also brought criminal and civil charges against Lilly after the company promoted Zyprexa for treatments the FDA had not approved. These included the treatment of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

In 2009, Lilly pleaded guilty to the federal charges against the company. It agreed to pay more than $1.4 billion to resolve the case. This included an $800-million civil settlement with the DOJ and a criminal fine of $515 million – the largest ever in a health care case at the time.

The company is believed to be shielded from liability in a joint venture with Japanese drug maker Takeda that resulted in another multi-billion dollar court settlement. In 1999, the FDA approved Actos (pioglitazone) to treat type 2 diabetes in the U.S. Developed by Takeda and marketed in the U.S. by Eli Lilly until 2006, Actos became one of the best-selling drugs in the world for a short time. But studies and reports of serious side effects prompted the FDA to conclude that it could increase the risk of bladder cancer in people who took it.

Takeda agreed to settle more than 10,000 Actos lawsuits for $2.4 billion in 2015. Lilly said in its 2016 annual report that its business agreement with Takeda required the Japanese company to “defend and indemnify us against our losses and expenses” in the U.S. lawsuits.

The drug Cymbalta (duloxetine) also led to lawsuits when people taking it developed medical complications when they stopped taking it. Withdrawal symptoms could sometimes be life-threatening. These included extreme mood swings and physical or neurological problems.

In 2009, the FDA termed the withdrawal symptoms “Cymbalta discontinuation syndrome” in a review of the drug. The agency said it was “more severe and much more widespread than acknowledged” by the company.

The FDA also found Lilly had not adequately warned people about just how serious these symptoms could be. The agency required Lilly to take several steps to improve warnings, including setting up a system to collect complaints about the drug.

In 2016, Lilly said it had established a settlement framework to settle the nearly 140 lawsuits still pending in various U.S. courts over injuries from Cymbalta.

Calling this number connects you with a Drugwatch representative. We will direct you to one of our trusted legal partners for a free case review.

Drugwatch's trusted legal partners support the organization's mission to keep people safe from dangerous drugs and medical devices. For more information, visit our partners page.