Takeda Pharmaceuticals

With more than $30 billion in revenue in 2021, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company is Japan’s largest drug manufacturer, and one of the 20 largest pharmaceutical companies in the world.

Founded as an herbal medicine shop more than 200 years ago, two centuries of steady growth, followed by rapid expansion since the late 1990s, have allowed Takeda to expand to more than 70 countries worldwide.

The company’s core business is built around therapeutic drugs treating four groups of conditions — gastrointestinal disorders, central nervous system (CNS) conditions, cardiovascular or metabolic conditions and cancer — along with a strategy of expansion into emerging markets.

Takeda’s emerging market thrust has been aided by expanding its vaccine divisions in recent years as a spearhead into more than 35 developing countries. At the same time, the company has joined United Nations initiatives and adopted the UN’s sustainable development goals (SDGs) as they apply to medicines and preventing disease. Takeda has made it a part of the company’s business model to address access to medicine and reducing barriers to health care in developing countries and other emerging markets.

The approach resulted in 4.8 percent revenue growth in Takeda’s emerging markets sector in 2015. At $2.9 billion, it was second only to Takeda’s cancer sector in overall revenue for the year.

The company’s general medicine products also include a portfolio of drugs to treat gout and diabetes. Its best-known drug marketed in the U.S. may be the heartburn medicine Prevacid. It is a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), part of a class of drugs that includes rivals Nexium and Prilosec.

Takeda History: Herbal Medicine Shop to Global Pharmaceutical Company

Chobei Takeda began selling traditional Japanese and Chinese herbal medicines from a small shop in Osaka, Japan in 1781. His great-grandson, Chobei Takeda IV, began importing western medicines into Japan in 1871, including the anti-malaria drug quinine and cholera medicine phenol.

The family business was renamed the Takeda Pharmaceutical Company in 1915, establishing research and testing divisions. It was incorporated in 1925 as Chobei Takeda & Co., Ltd., as a modern corporate organization, and later to Takeda Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd. in 1943.

After World War II, as Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Ltd., it turned toward overseas expansion, building new factories, becoming a publicly traded company, and building joint partnerships with other companies. It produced antibiotics and developed vitamins to supplement nutrition for people afflicted by post-war food shortages.

In the 1960s, Takeda expanded across Asia, building factories and establishing marketing companies in Taiwan, the Philippines, Thailand and Indonesia. In the 1970s, the company expanded sales to Europe, marketing products to France, Germany and Italy. This expansion led to Takeda’s focus on globalization — manufacturing and marketing its drugs around the world.

In 1997 and 1998, Takeda established corporate entities in the UK, Ireland and the U.S. Its global growth and restructuring would continue into the new century as Takeda integrated other companies. New companies were integrated to expand marketing and researching new drugs and treatment options.

| Year | Company | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | Syrrx, Inc. (U.S.) | Drug discovery |

| 2007 | Paradigm Therapeutics Limited (Singapore) | Drug discovery |

| 2008 | TAP Pharmaceutical Products, Inc. (U.S.) | Drug marketing and development |

| 2008 | Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (U.S.) | Cancer treatment research and development |

| 2011 | Nycomed (Switzerland) | Access to pharmaceutical markets in 70 countries |

| 2012 | URL Pharma, Inc. (U.S.) | Gout treatment |

| 2012 | Multilab (Brazil) | Expansion of sales and presence in Brazil |

| 2012 | LigoCyte Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (U.S.) | Vaccines |

| 2012 | Envoy Therapeutics, Inc. (U.S.) | Drug discovery |

Actos: Expensive Problems for Takeda’s Blockbuster Drug

As Takeda acquired other companies to expand its pharmaceutical portfolio and market share, the company was also busy rolling out a series of new drugs. These included medications that expanded beyond its core therapeutic drug focus.

As the company pushed forward with new growth, some of its older products led to allegations the company was putting profits ahead of patients. Two of its drugs, in particular, would raise health concerns and one would feature into thousands of lawsuits against the company.

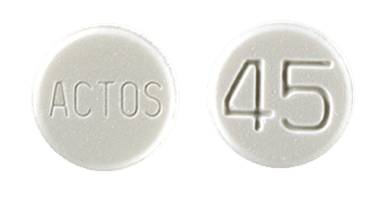

Actos (pioglitazone) was one of Takeda’s first blockbuster drugs. At one time, it was the most prescribed drug for Type 2 diabetes in the world. Sales peaked in 2010 at $4.5 billion — accounting for 27 percent of Takeda’s revenues.

In the years after it hit the U.S. market, several studies found an increased risk of bladder cancer among patients taking Actos. In 2011, the FDA required heightened warnings about the cancer risk on Actos labels. By 2012, thousands of lawsuits had been filed against Takeda over Actos.

In 2014, Takeda settled 9,000 lawsuits for a total of $2.4 billion. The settlement would contribute to a $1.3 billion net loss in company profits for the year.

Takeda was already reeling from the U.S. patent on Actos expiring in 2012. The same month it expired, Israel-based Teva, the world’s largest generic drug manufacturer announced a generic version of the drug.

In 2016, Takeda entered a joint venture with Teva. The Israeli company will manufacture some of Takeda’s best selling drugs as patents expire. The plan is to reduce financial losses to generic competition as Takeda products go off-patent.

Takeda Pioneered a Class of Drugs Drawing Increased Scrutiny

Gastrointestinal medicines are one of the three core areas of Takeda’s pharmaceutical business model. Takeda developed and marketed one of the world’s first two proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) — a class of powerful heartburn drugs.

Takeda launched Lansoprazole in Europe in 1991. It received FDA approval in 1995 as Prevacid. The drug is sold in 90 countries around the world today.

Takeda’s other proton pump inhibitors include Protonix, approved in 2000, and Dexilant, approved in 2009.

PPIs are only supposed to be used for two-week treatments and no more than three times a year. Health care professionals have frequently been critical of marketing efforts and studies have questioned whether the drugs are over prescribed.

Other studies have associated the drugs with serious kidney-related conditions as well as risks of strokes, bone fractures and serious infections.

Takeda Drug Recalls Include Rare Patient Deaths

In November 2010, Takeda’s recently acquired Millennium Pharmaceuticals recalled thousands of units of the cancer drug Velcade sold in the U.S., Europe, Japan and Malaysia.

White particles, later identified as “polyester-like material” from the manufacturing process, were seen floating in vials of the drug. Velcade is used to treat multiple myeloma. The recall affected more than 50,000 vials in distribution at the time, including 10,000 in the U.S.

In February 2013, Takeda, and partner company Affymax, Inc., recalled all lots of anemia drug Omontys after reports of severe reactions that sometimes ended in patient deaths. The injectable drug was used to treat dialysis patients.

The companies conducted a review of the drug but could not determine what caused the reaction. In June 2014, Affymax and Takeda dissolved their marketing and licensing partnership and Takeda withdrew its new drug application for Omontys from FDA consideration.

In July 2015, Takeda and partner Orexigen recalled about 3,600 bottles of obesity drug Contrave because the tablets could split into two drug components. Orexigen manufactured Contrave and Takeda was providing marketing resources for it.

In March 2016, Takeda withdrew from its partnership with Orexigen. Takeda blamed the California-based company for botching a postmarketing trial of the drug — costing the partnership millions of dollars.

Takeda was no longer associated with the drug when the FDA added Contrave to its watch list of drugs with possible safety issues in April 2017. The agency said it had received reports of patients losing consciousness after taking the drug.

| Year | Medication | Indicated for: |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | Rozerem | Insomnia |

| 2009 | Uloric | Excess uric acid in people with gout |

| 2009 | Dexilant | Excess stomach acid (a proton pump inhibitor) |

| 2013 | Nesina | Type 2 diabetes |

| 2013 | Trintellix | Depression |

| 2014 | Entyvio | Inflammatory bowel disease, for people who fail to respond to other treatments |

| 2015 | NINLARO | Multiple myeloma (cancer formed by malignant plasma cells), used in combination with other cancer treatment medicines |

| 2017 | Alunbrig | ALK-positive cases of non-small cell lung cancer (cancer caused by a genetic abnormality) |

Calling this number connects you with a Drugwatch representative. We will direct you to one of our trusted legal partners for a free case review.

Drugwatch's trusted legal partners support the organization's mission to keep people safe from dangerous drugs and medical devices. For more information, visit our partners page.