Metallosis & Metal Poisoning

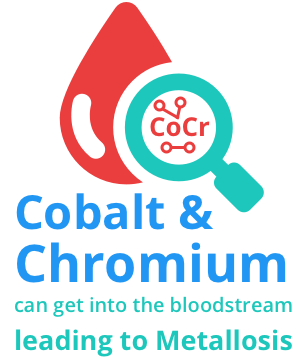

Metallosis is a condition caused by the buildup and shedding of metal debris, which occurs when metal joint replacement devices rub against each other and release metal ions into the bloodstream, bone and tissue surrounding the implant.

Metallosis is a type of metal poisoning that can occur as a side effect of joint replacement devices with metal components, such as metal-on-metal hip replacements or other metal implants. These devices are made from a blend of several metals, including chromium, cobalt, nickel, titanium and molybdenum. When the metal parts rub against each other, they release microscopic metal particles into the blood and surrounding tissues.

A 2022 study reported that, following a hip replacement, 46.7% of participants experienced a clinically significant improvement, while 15.5% experienced worsened outcomes.

Metallosis develops as these metal ions build up in the bone, muscle and other tissue around the implant. This can result in death of bone or other tissue.

Exposure to metal in the blood and surrounding tissues can lead to several other complications. Buildup of cobalt or other metals can affect the brain, heart, eyes, and other organs.

Treating metallosis and related conditions usually requires revision surgery to remove and replace the metal implant.

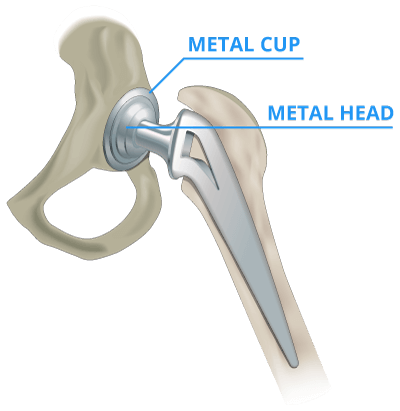

Some metal-on-metal hip implants, such as the DePuy ASR, used a metal ball and cup. Others, such as the Stryker Rejuvenate and ABG II, used a metal neck and stem. Metal-on-metal hips contained components made of cobalt and chromium.

Metallosis Symptoms Following Hip Replacement

Local symptoms of metallosis include hip or groin pain, numbness, swelling, weakness and a change in the ability to walk, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. You may notice problems with your skin, heart, kidneys, nervous system or thyroid before you experience local symptoms.

A 2012 article in Current Orthopaedic Practice by Dr. James Pritchett identified early metallosis symptoms as “a feeling of instability, an increase in audible sounds from the hip, and pain that was not present immediately after surgery.”

If patients don’t address these symptoms, metallosis can advance to bone loss and tissue death around the implant. The only treatment for metallosis is surgery.

Pain following the initial hip replacement surgery is not always an indicator of metallosis. For example, a study of 116 hip resurfacing patients found that 18 percent reported groin pain following surgery, but asserted that the “cause is most likely multifactorial, ranging from iliopsoas tendinitis to an adverse soft tissue reaction.”

Pritchett also cited a 1975 study, published in The British Editorial Society of Bone and Joint Surgery, that stated “cobalt toxicity [metallosis] may begin from nine months to four years after operation.”

Metal-on-Metal Hips and Cancer

A link between cancer and the metal particles from hip implants has not been proven.

A 2012 study in the British Medical Journal compared 10,728 patients who’d received a metal-on-metal hip with 18,235 who had received a more conventional hip replacement.

Researchers found the risk of cancer was similar for both groups.

But the World Health Organization International Agency for Research on Cancer lists both cobalt and trivalent, a type of chromium, as potential cancer-causing substances.

After thousands of metal-on-metal implants failed, the London Implant Retrieval Centre released test results confirming that the implants released trivalent chromium ions. So while no increased cancer risk has been found, metal-on-metal hip implants may release particles that potentially cause cancer.

Cobalt & Chromium Hip Implants

Metal-on-metal hip implants were often constructed with cobalt and chromium. The body naturally stores a certain level of cobalt and chromium for healthy cellular function. Cobalt is a part of vitamin B12, needed to produce red blood cells. But plants, animals and humans need only tiny amounts of it to survive. Excessive amounts of cobalt can lead to metal poisoning.

People can get cobalt poisoning by breathing in too much cobalt, swallowing too much of it or having prolonged skin contact with it. Manufacturers use cobalt in products such as dyes, batteries, alloys and machine tools.

When metal implant components rub together, they can release cobalt and chromium ions above those natural levels.

Ingesting or inhaling too much cobalt may lead to deafness, thyroid problems, nerve problems and heart problems. The same problems can occur in hip implant patients if the amount of metal ions in the blood is excessive.

- Cardiomyopathy (heart problems), including heart failure

- Depression and other mental health conditions

- Visual impairment that may lead to blindness

- Cognitive impairment

- Nerve problems, such as peripheral neuropathy

- Thyroid problems

- Auditory impairment, tinnitus, deafness

- Skin rashes

- Thickening of the blood

- Implant loosening

When excessive cobalt is released, the body may excrete some of it quickly. What isn’t excreted is absorbed by the blood and distributed to tissues throughout the body, mainly to the kidney, liver and bones. In the case of metal implants, the tissue around the implant absorbs the excess cobalt where it can build up.

Severe Metallosis Cases

In 2010, the Alaska Epidemiology Bulletin published a report of metallosis-related symptoms identified in two fit, healthy 49-year-old men who had received metal-on-metal implants. Orthopedic surgeon Stephen S. Tower wrote about the case studies.

- Anxiety

- Groin pain

- Headaches

- Hearing loss

- Heart irregularities

- Irritability

- Poor memory and mental fogginess

- Shortness of breath

- Skin rashes

- Tinnitus

- Vertigo

Source: Alaska Epidemiology Bulletin, May 28, 2010

Despite normal kidney function, both men had toxic levels of cobalt in the blood. Each patient had revision surgery, which revealed tissue death around the implants. Tower described “staining with metal debris” in the tissue surrounding the implants in both men. The implants also showed signs of wear.

Both men saw significant improvement in most of their symptoms within a few months after the faulty implants were removed. But one of the patients, who’d lost part of his vision, had not recovered his previous vision at six months after surgery.

Diagnosing Metallosis

Doctors may rely on soft tissue imaging or metal ion testing to determine if a patient has excess metal ions in their system, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Each can provide evidence of tissue damage from metal ions, but neither of these should be used as the only test of whether a hip is failing due to metallosis.

Soft tissue imaging includes MRIs and CT and ultrasound scans. Each method has advantages and shortcomings. The metal in metal-on-metal hips can create distortions in the imaging field of MRIs and CT scans. Ultrasounds allow doctors to see the tissue without the metal interference, but they have a lower resolution and don’t show imaging as deep under the skin as the MRIs or CTs.

A doctor may also use a blood test to check for cobalt, chromium, molybdenum and titanium, all metals used in metal-on-metal hips. The FDA recommends that any test should be able to measure ion levels as low as one part per billion, or ppb. That means one part metal ions for every one billion parts of blood.

In the past, the threshold was 7 times higher. But as of 2019, the FDA recommends the much smaller amount as a threshold. The agency found that some patients above the 7.0 ppb threshold showed no symptoms, while some below it already exhibited metal-on-metal hip complications.

The FDA also lays out guidance for doctors on choosing a lab to conduct the blood samples and how to interpret the lab results.

Who Should Be Tested?

Anyone who currently has a metal-on-metal hip implant is at some risk of developing metallosis. But not everyone who has a metal-on-metal hip will develop metallosis or other symptoms associated with implant wear.

The U.S Food and Drug Administration recommends that doctors test for excessive ion levels if patients exhibit symptoms of any of six conditions.

Symptoms Warranting Metal Ion Testing

- Skin rash or other hypersensitive reaction

- Cardiomyopathy, a chronic disease of the heart tissue

- Neurological changes, including impairment of hearing or vision

- Psychological changes, including depression and cognitive impairment

- Problems with kidney function

- Thyroid dysfunction, including neck discomfort, fatigue, weight gain or feeling cold

Source: U.S. Food and Drug Administration

The FDA does not recommend testing for people who have not exhibited symptoms of these conditions so long as their orthopedic surgeon determines the hip is functioning properly.

Metallosis Treatment

Surgery to remove and replace the worn metal-on-metal is the only treatment for metallosis. It stops the release of further metal ions. The doctor will remove diseased bone and tissue around the implant.

With severe metallosis, the amount of tissue and bone necrosis, or death, determines the outcome of the surgery. Some patients suffer fractures during revision surgery because of weak bones and extensive tissue damage. During revision surgery, surgeons replace the metal-on-metal implant with a ceramic-on-metal or plastic-on-metal implant to minimize future problems with metal ions.

Some patients may see drastic improvement of their symptoms in three to six months following revision surgery, according to case studies published in the State of Epidemiology Bulletin.

Metallosis and the FDA

In February 2016, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration raised the bar to get a metal-on-metal hip implant approved. It now requires manufacturers to go through the agency’s most stringent approval process before selling the devices in the United States.

Manufacturers now have to show the FDA that a new metal-on-metal hip is backed up by valid scientific evidence showing it is safe and effective for its intended use. The FDA also requires companies to get the agency’s approval before making any changes to the implant, its labels or how it’s manufactured. Manufacturers also have to meet certain reporting requirements to the FDA every year.

Prior to the new requirements, most metal-on-metal hips were cleared through the FDA’s 510(k) clearance process. Makers did not have to prove their new device was safe and effective, merely that it was “substantially similar” to another device already on the market.

Most manufacturers discontinued metal-on-metal hip implant products or issued hip replacement recalls after thousands of patients were injured by the devices. Patients injured by metallosis or other complications also filed tens of thousands of hip replacement lawsuits over defective devices.

As of March 2019, there are no metal-on-metal total hip replacements approved for use in the United States. The FDA, however, has approved two metal-on-metal hip resurfacing systems.

Calling this number connects you with a Drugwatch representative. We will direct you to one of our trusted legal partners for a free case review.

Drugwatch's trusted legal partners support the organization's mission to keep people safe from dangerous drugs and medical devices. For more information, visit our partners page.